Types of Banks/Classification of Banks

Types of Banks Classification of Banks in India

Types of Banks

UNIVERSAL BANK

It is financial supermarket where all financial products are sold under one roof.

• It is a system of banking where bank undertake a blanket of financial services like investment banking, commercial banking, development banking, insurance and other financial services including functions of merchant banking, mutual funds, factoring, housing finance etc.

• As per the World Bank, the definition of the Universal Bank is as follows: In Universal banking, the large banks operate extensive network of branches, provide many different services, hold several claims on firms (including equity and debt) and participate directly in the Corporate Governance of firms that rely on the banks for funding or as insurance underwriters.

• The second Narasimham committee of 1998 gave an introductory remark on the concept of the Universal banking, as a different concept than the Narrow Banking. Narsimham Committee II suggested that Development Financial Institutions (DFIs) should convert ultimately into either commercial banks or non-bank finance companies.

• However, the concept of Universal Banking conceptualized in India after the RH Khan Committee recommended it as a different concept. The Khan Working Group held the view that DFIs (Development Finance Institutions) should beallowed to become banks at the earliest.

It is financial supermarket where all financial products are sold under one roof.

• It is a system of banking where bank undertake a blanket of financial services like investment banking, commercial banking, development banking, insurance and other financial services including functions of merchant banking, mutual funds, factoring, housing finance etc.

• As per the World Bank, the definition of the Universal Bank is as follows: In Universal banking, the large banks operate extensive network of branches, provide many different services, hold several claims on firms (including equity and debt) and participate directly in the Corporate Governance of firms that rely on the banks for funding or as insurance underwriters.

• The second Narasimham committee of 1998 gave an introductory remark on the concept of the Universal banking, as a different concept than the Narrow Banking. Narsimham Committee II suggested that Development Financial Institutions (DFIs) should convert ultimately into either commercial banks or non-bank finance companies.

• However, the concept of Universal Banking conceptualized in India after the RH Khan Committee recommended it as a different concept. The Khan Working Group held the view that DFIs (Development Finance Institutions) should beallowed to become banks at the earliest.

Advantages of Universal Banking

• Increased diversions and increased profitability.

• Better Resource Utilization.

• Brand name leverage.

• Existing clientele leverage.

• Value added services.

• ‘One-stop shopping’ saves a lot of transaction costs.

• Easy Marketing

• Profit Diversification

• Increased diversions and increased profitability.

• Better Resource Utilization.

• Brand name leverage.

• Existing clientele leverage.

• Value added services.

• ‘One-stop shopping’ saves a lot of transaction costs.

• Easy Marketing

• Profit Diversification

DEVELOPMENT BANK

• Development bank is essentially a multi-purpose financial institution with a broad development outlook.

• A development bank may, thus, be defined as a financial institution concerned with providing all types of financial assistance (medium as well as long term) to business units, in the form of loans, underwriting, investment and guarantee operations, and promotional activities — economic development in general, and industrial development, in particular.

• Development bank is essentially a multi-purpose financial institution with a broad development outlook.

• A development bank may, thus, be defined as a financial institution concerned with providing all types of financial assistance (medium as well as long term) to business units, in the form of loans, underwriting, investment and guarantee operations, and promotional activities — economic development in general, and industrial development, in particular.

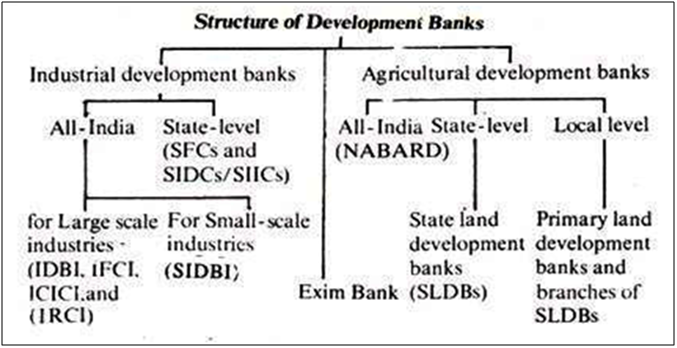

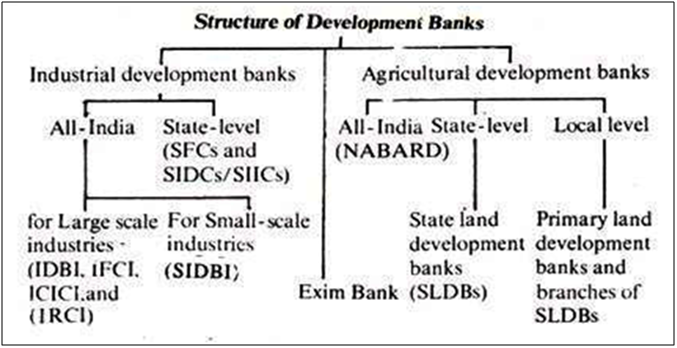

Development banks in India are classified into following four groups:

Industrial Development Banks: It includes, for example, Industrial Finance Corporation of India (IFCI), Industrial Development Bank of India (IDBI), and Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI).

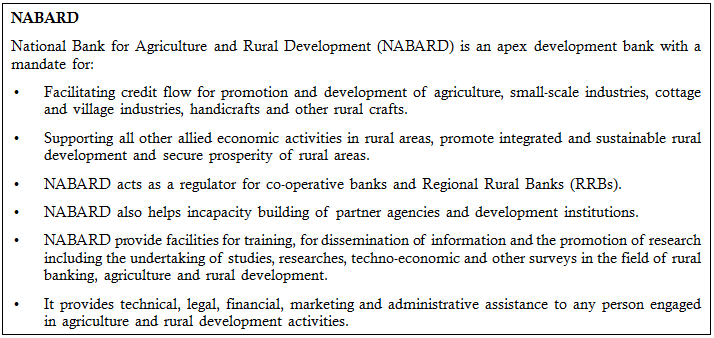

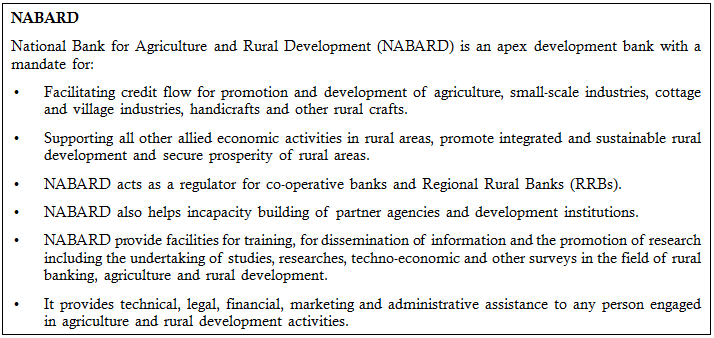

Agricultural Development Banks: It includes, for example, National Bank for Agriculture & Rural Development (NABARD).

Export-Import Development Banks: It includes, for example, Export-Import Bank of India (EXIM Bank).

Housing Development Banks: It includes, for example, National Housing Bank (NHB).

Industrial Development Banks: It includes, for example, Industrial Finance Corporation of India (IFCI), Industrial Development Bank of India (IDBI), and Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI).

Agricultural Development Banks: It includes, for example, National Bank for Agriculture & Rural Development (NABARD).

Export-Import Development Banks: It includes, for example, Export-Import Bank of India (EXIM Bank).

Housing Development Banks: It includes, for example, National Housing Bank (NHB).

LEAD BANK

Introduced in 1969, based on the recommendations of the Gadgil Study Group on the organizational framework for the implementation of social objectives.

Introduced in 1969, based on the recommendations of the Gadgil Study Group on the organizational framework for the implementation of social objectives.

Objectives of Lead Bank Scheme:

• Eradication of unemployment and under employment

• Appreciable rise in the standard of living for the poorest of the poor

• Provision of some of the basic needs of the people who belong to poor sections of the society.

• Eradication of unemployment and under employment

• Appreciable rise in the standard of living for the poorest of the poor

• Provision of some of the basic needs of the people who belong to poor sections of the society.

Area Approach

• The basic idea was to have an “area approach” for targeted and focused banking.

• The banker’s committee, headed by S. Nariman, concluded that districts would be the units for area approach and each district could be allotted to a particular bank which will perform the role of a Lead Bank.

• The Lead bank Scheme was not fully able to achieve its targets due to shift in policies, complexities in operations, lack of cooperation among various financial institutions and issues shifting to the Financial Inclusion.

• There was a strong need felt to revitalize the scheme with clear guidelines on respecting the bankers’ commercial judgements even as they fulfill their sectoral targets.

• The Government of India constituted a High-Power Committee headed by Mrs. Usha Thorat, Deputy Governor of the RBI, to suggest reforms in the LBS. The task of this penal was to recommend how to revitalize the LBS, given the challenges facing the banking sector, especially in an era of increasing privatization and autonomy.

• The basic idea was to have an “area approach” for targeted and focused banking.

• The banker’s committee, headed by S. Nariman, concluded that districts would be the units for area approach and each district could be allotted to a particular bank which will perform the role of a Lead Bank.

• The Lead bank Scheme was not fully able to achieve its targets due to shift in policies, complexities in operations, lack of cooperation among various financial institutions and issues shifting to the Financial Inclusion.

• There was a strong need felt to revitalize the scheme with clear guidelines on respecting the bankers’ commercial judgements even as they fulfill their sectoral targets.

• The Government of India constituted a High-Power Committee headed by Mrs. Usha Thorat, Deputy Governor of the RBI, to suggest reforms in the LBS. The task of this penal was to recommend how to revitalize the LBS, given the challenges facing the banking sector, especially in an era of increasing privatization and autonomy.

The following were the recommendation of Usha Thorat Committee on Lead Banks

• LBS should be continued to accelerate financial inclusion in the unbanked areas of the country.

• Private sector banks should be given a greater role in LBS action plans, particularly in areas of their presence.

• Enhance the business correspondent model, making banking services available in all villages having a population of above 2,000 and relaxation in KYC (know your customer) norms for small value accounts.

• There is a strong need to revamp and revitalise the Lead Bank Scheme so as to make it an effective instrument for bringing about meaningful co-ordination among banks operating in various part of the country.

• LBS should be continued to accelerate financial inclusion in the unbanked areas of the country.

• Private sector banks should be given a greater role in LBS action plans, particularly in areas of their presence.

• Enhance the business correspondent model, making banking services available in all villages having a population of above 2,000 and relaxation in KYC (know your customer) norms for small value accounts.

• There is a strong need to revamp and revitalise the Lead Bank Scheme so as to make it an effective instrument for bringing about meaningful co-ordination among banks operating in various part of the country.

PAYMENT BANK

• A payments bank is like any other bank, but operating on a smaller scale without involving any credit risk.

• In simple words, it can carry out most banking operations but can’t advance loans or issue credit cards.

• It can accept demand deposits (up to Rs 1 Lakh), offer remittance services, mobile payments/transfers/purchases and other banking services like ATM/debit cards, net banking and third party fund transfers.

• The NachiketMor committee appointed by RBI to propose measures for achieving financial inclusion and increased access to financial services in 2013.The committee submitted its report suggesting creation of specialized bank or Payment Bank to cater the lower income groups and small businesses so that by Jan 2016, each Indian resident can have a global bank account.

• A payments bank is like any other bank, but operating on a smaller scale without involving any credit risk.

• In simple words, it can carry out most banking operations but can’t advance loans or issue credit cards.

• It can accept demand deposits (up to Rs 1 Lakh), offer remittance services, mobile payments/transfers/purchases and other banking services like ATM/debit cards, net banking and third party fund transfers.

• The NachiketMor committee appointed by RBI to propose measures for achieving financial inclusion and increased access to financial services in 2013.The committee submitted its report suggesting creation of specialized bank or Payment Bank to cater the lower income groups and small businesses so that by Jan 2016, each Indian resident can have a global bank account.

Objectives of Payment Bank

• To widen the spread of payment and financial services to small businesses, low income households, migrant labour workforce in secured technology driven environment.

• With payments banks, RBI seeks to increase the penetration level of financial services to the remote areas of the country.

• To widen the spread of payment and financial services to small businesses, low income households, migrant labour workforce in secured technology driven environment.

• With payments banks, RBI seeks to increase the penetration level of financial services to the remote areas of the country.

SMALL FINANCE BANK

Small finance banks are a type of niche banks in India. The main purpose of the small banks will be to provide a whole suite of basic banking products such as bank deposits and supply of credit, but in a limited area of operation. The objective for these Small Banks is to increase financial inclusion by provision of savings vehicles to under-served and unserved sections of the population, supply of credit to small farmers, micro and small industries, and other unorganized sector entities through high technology-low cost operations.

Small finance banks are a type of niche banks in India. The main purpose of the small banks will be to provide a whole suite of basic banking products such as bank deposits and supply of credit, but in a limited area of operation. The objective for these Small Banks is to increase financial inclusion by provision of savings vehicles to under-served and unserved sections of the population, supply of credit to small farmers, micro and small industries, and other unorganized sector entities through high technology-low cost operations.

RBI guidelines about small bank includes:

• The firms must have a capital of Indian Rupees 100 crore. Existing Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFC), Micro-Finance Institutions (MFI) and Local Area Banks (LAB) are allowed to set up small finance banks.

• The Corporate Promoter should have 10 years experience in banking and finance.

• The promoters stake in the paid-up equity capital will be 40% initially which must be brought down to 26% in 12 years. Joint ventures are not permitted.

• Foreign share holding will be allowed in these banks as per the rules for Foreign Direct Investment in private banks in India.

• The banks will not be restricted to any region. 75% of its net credits should be in priority sector lending and 50% of the loans in its portfolio must in 25 lakh range.

• The bank shall primarily undertake basic banking activities of accepting deposits and lending to small farmers, small businesses, micro and small industries, and unorganized sector entities. It cannot set up subsidiaries to undertake non-banking financial services activities. After the initial stabilization period of 5 years, and after a review, the RBI may liberalize the scope of activities for Small Banks.

• Small Banks have to meet RBI’s norms and regulations regarding risk management. They have to meet CRR, SLR, Repo rate and reverse repo rate requirements, like any other commercial bank.

• The maximum loan size and investment limit exposure to single/group borrowers/issuers would be restricted to 15% of capital funds.

• For the first 3 years, 25% of branches should be in unbanked rural areas.

• The firms must have a capital of Indian Rupees 100 crore. Existing Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFC), Micro-Finance Institutions (MFI) and Local Area Banks (LAB) are allowed to set up small finance banks.

• The Corporate Promoter should have 10 years experience in banking and finance.

• The promoters stake in the paid-up equity capital will be 40% initially which must be brought down to 26% in 12 years. Joint ventures are not permitted.

• Foreign share holding will be allowed in these banks as per the rules for Foreign Direct Investment in private banks in India.

• The banks will not be restricted to any region. 75% of its net credits should be in priority sector lending and 50% of the loans in its portfolio must in 25 lakh range.

• The bank shall primarily undertake basic banking activities of accepting deposits and lending to small farmers, small businesses, micro and small industries, and unorganized sector entities. It cannot set up subsidiaries to undertake non-banking financial services activities. After the initial stabilization period of 5 years, and after a review, the RBI may liberalize the scope of activities for Small Banks.

• Small Banks have to meet RBI’s norms and regulations regarding risk management. They have to meet CRR, SLR, Repo rate and reverse repo rate requirements, like any other commercial bank.

• The maximum loan size and investment limit exposure to single/group borrowers/issuers would be restricted to 15% of capital funds.

• For the first 3 years, 25% of branches should be in unbanked rural areas.

Economic Survey Chapter – 4

The Festering Twin Balance Sheet Problem

The Festering Twin Balance Sheet Problem (Economic Survey Chapter – 4)

Context

For some time, India has been trying to solve its Twin Balance Sheet problem-overleveraged companies and bad-loan-encumbered banks. NPAs continued to climb, reaching 9 percent of total advances by September (80% in PSB’s). At the same time corporate profitability has reduced, their cash ?ows are deteriorating even as their interest obligations are mounting. The reason is corporations over-expand during a boom, but combination of financial crisis, delayed clearances and increasing interests left them with obligations that they can’t repay. So, they default on their debts, leaving bank balance sheets impaired, as well.

This combination then proves devastating for growth, since the hobbled corporations are reluctant to invest, while those that remain sound can’t invest much either, since fragile banks are not really in a position to lend to them. This has spill over effect in terms of higher cost of loans to performing borrowers and shrinking growth of loans to MSME sector. One possible strategy would be to create a ‘Public Sector Asset Rehabilitation Agency’ (PARA), charged with working out the largest and most complex cases. However, its success depends on staffing professionals of impeccable integrity and delinking its actions from political consequences.

This combination then proves devastating for growth, since the hobbled corporations are reluctant to invest, while those that remain sound can’t invest much either, since fragile banks are not really in a position to lend to them. This has spill over effect in terms of higher cost of loans to performing borrowers and shrinking growth of loans to MSME sector. One possible strategy would be to create a ‘Public Sector Asset Rehabilitation Agency’ (PARA), charged with working out the largest and most complex cases. However, its success depends on staffing professionals of impeccable integrity and delinking its actions from political consequences.

Technical Terms

A. Over-leveraged firms – If a company is overleveraged, it has borrowed too much money and cannot make payments on the debt.

B. Stressed assets = NPAs + Restructured loans + Written off assets

• NPA – A loan whose interest and/or instalment of principal have remained ‘overdue ‘ (not paid) for a period of 90 days is considered as NPA.

• Restructured asset or loan – They are that assets which got an extended repayment period, reduced interest rate, converting a part of the loan into equity, providing additional financing, or some combination of these measures.

• Written off assets – They are those loans/assets bank or lender doesn’t count the money borrower owes to it. The financial statement of the bank will indicate that the written off loans are compensated through some other way. There is no meaning that the borrower is pardoned or got exempted from payment.

C. Asset Quality Review – Typically, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) inspectors check bank books every year as part of its annual financial inspection (AFI) process. However, a special inspection was conducted in 2015-16 in the August-November period. This was named as Asset Quality Review (AQR). In a routine AFI, a small sample of loans is inspected to check if asset classification was in line with the loan repayment and if banks have made provisions adequately. However, in the AQR, the sample size was much bigger and in fact, most of the large borrower accounts were inspected to check if classification was in line with prudential norms. The RBI believed that asset classification was not being done properly and that banks were resorting to ever-greening of accounts. Banks were postponing bad-loan classification and deferring the inevitable.

D. Ever-greening of Loan – Ever-greening refers to the practice of companies taking a fresh loan to pay up an old loan.

E. Principal agent problem – The problem of motivating one party (the agent) to act on behalf of another (the principal) is known as the principal-agent problem, or agency problem for short. The principle agent problem arises when one party (agent) agrees to work in favor of another party (principal) in return for some incentives. Such an agreement may incur huge costs for the agent, thereby leading to the problems of moral hazard and conflict of interest. Owing to the costs incurred, the agent might begin to pursue his own agenda and ignore the best interest of the principal, thereby causing the principal agent problem to occur.

B. Stressed assets = NPAs + Restructured loans + Written off assets

• NPA – A loan whose interest and/or instalment of principal have remained ‘overdue ‘ (not paid) for a period of 90 days is considered as NPA.

• Restructured asset or loan – They are that assets which got an extended repayment period, reduced interest rate, converting a part of the loan into equity, providing additional financing, or some combination of these measures.

• Written off assets – They are those loans/assets bank or lender doesn’t count the money borrower owes to it. The financial statement of the bank will indicate that the written off loans are compensated through some other way. There is no meaning that the borrower is pardoned or got exempted from payment.

C. Asset Quality Review – Typically, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) inspectors check bank books every year as part of its annual financial inspection (AFI) process. However, a special inspection was conducted in 2015-16 in the August-November period. This was named as Asset Quality Review (AQR). In a routine AFI, a small sample of loans is inspected to check if asset classification was in line with the loan repayment and if banks have made provisions adequately. However, in the AQR, the sample size was much bigger and in fact, most of the large borrower accounts were inspected to check if classification was in line with prudential norms. The RBI believed that asset classification was not being done properly and that banks were resorting to ever-greening of accounts. Banks were postponing bad-loan classification and deferring the inevitable.

D. Ever-greening of Loan – Ever-greening refers to the practice of companies taking a fresh loan to pay up an old loan.

E. Principal agent problem – The problem of motivating one party (the agent) to act on behalf of another (the principal) is known as the principal-agent problem, or agency problem for short. The principle agent problem arises when one party (agent) agrees to work in favor of another party (principal) in return for some incentives. Such an agreement may incur huge costs for the agent, thereby leading to the problems of moral hazard and conflict of interest. Owing to the costs incurred, the agent might begin to pursue his own agenda and ignore the best interest of the principal, thereby causing the principal agent problem to occur.

Gist of Economic Survey Chapter

The chapter look into the Twin Balance Sheet (TBS) problem of India. After Asset Quality Review (AQR) by RBI, in early 2016 it became clear that India was suffering from a “twin balance sheet problem”, where both the banking and corporate sectors were under stress.

Why TBS problem did not create bank runs during crisis?

Typically, countries with a twin balance sheet (TBS) problem follow a standard path. Their corporations over-expand during a boom, leaving them with obligations that they can’t repay. So, they default on their debts, leaving bank balance sheets impaired, as well. This combination then proves devastating for growth, since the hobbled corporations are reluctant to invest, while those that remain sound can’t invest much either, since fragile banks are not really in a position to lend to them. 4.8 This model, however, doesn’t seem to fit India’s case.

India’s TBS problem is unique, because it did not come to surface during Global Financial Crisis (2008) and even economy continued to grow at good pace. This was mainly because most of NPA’s were concentrated in the public sector banks, which not only hold their own capital, but are ultimately backed by the government, whose resources are more than sufficient to deal with the NPA problem. As a result, creditors have retained complete confidence in the banking system.

In this scenario to understand India’s TBS problem four set of Questions need to be answered.

• What went wrong – and when did it go wrong?

• How has India managed to achieve rapid growth, despite its TBS problem?

• Is this model sustainable?

• What now needs to be done?

What went wrong – and when did it go wrong?

During the mid-2000s i.e. at time of boom firms abandoned their conservative debt/equity ratios and leveraged themselves up to take advantage of the perceived opportunities, setting off the biggest investment boom financed by an astonishing credit boom in the country’s history, mainly from banks and large inflow of funds from overseas. But just as companies were taking on more risk, things started to go wrong.

• Costs soared far above budgeted levels, as securing land and environmental clearances proved much more difficult and time consuming than expected.

• At the same time, forecast revenues collapsed after the GFC; projects that had been built around the assumption that growth would continue at double-digit levels were suddenly confronted with growth rates half that level.

• Financing cost increased due to RBI increased interest rates to quell double digit inflation.

• For overseas financing rupee depreciated, forcing firms to repay debt at much high exchange rate.

Higher costs, lower revenues, greater financing costs — all squeezed corporate cash flow, quickly leading to debt servicing problems. By 2013, nearly one-third of corporate debt was owed by companies with an interest coverage ratio less than 1 (“IC1 companies”), many of them in the infrastructure (especially power generation) and metals sectors. By 2015, the share of IC1 companies reached nearly 40 percent.

How has India managed to achieve rapid growth, despite its TBS problem? (Twin Balance Sheet Syndrome with Indian Characteristics)

India followed the standard path to the TBS problem: a surge of borrowing, leading to over leverage and debt servicing problems. What distinguished India from other countries was the consequence of TBS. TBS did not lead to economic stagnation in India, as occurred in the U.S. and Europe after the Global Financial Crisis. To the contrary, it co-existed with strong levels of aggregate domestic demand, as reflected in high levels of growth despite very weak exports and moderate, at times high, levels of inflation. This is called as Balance sheet Syndrome with Indian Characteristics. This can be explained by following reasons:

• The unusual structure of its banking system (government backed public sector banks), which ensured there would be no financial crisis.

• As supply side constraints were loosened considerably during the boom, investment in infrastructure keep the pace of growth up even after GFC. In comparison, the US boom was based on housing construction, which proved far less useful after the crisis.

• Apart from it Indian financial system adopted the strategy of “give time to time”, meaning to allow time for the corporate wounds to heal. Thus banks decided to give stressed enterprises more time by postponing loan repayments, restructuring by 2014-15 no less than 6.4 percent of their loans outstanding. They also extended fresh funding to the stressed firms to tide them over until demand recovered

As a result, total stressed assets have far exceeded the headline figure of NPAs. Restructured loans along with unrecognised debt (loans owed by IC1 companies that have not even been recognised as problem debts – the ones that have been “ever greened”, where banks lend firms the money needed to pay their interest obligations) which are estimated at around 4 percent of gross loans, and perhaps 5 percent at public sector banks. In that case, total stressed assets would amount to about 16.6 per cent of banking system loans – and nearly 20 percent of loans at the state banks. Now the question raised is:

Typically, countries with a twin balance sheet (TBS) problem follow a standard path. Their corporations over-expand during a boom, leaving them with obligations that they can’t repay. So, they default on their debts, leaving bank balance sheets impaired, as well. This combination then proves devastating for growth, since the hobbled corporations are reluctant to invest, while those that remain sound can’t invest much either, since fragile banks are not really in a position to lend to them. 4.8 This model, however, doesn’t seem to fit India’s case.

India’s TBS problem is unique, because it did not come to surface during Global Financial Crisis (2008) and even economy continued to grow at good pace. This was mainly because most of NPA’s were concentrated in the public sector banks, which not only hold their own capital, but are ultimately backed by the government, whose resources are more than sufficient to deal with the NPA problem. As a result, creditors have retained complete confidence in the banking system.

In this scenario to understand India’s TBS problem four set of Questions need to be answered.

• What went wrong – and when did it go wrong?

• How has India managed to achieve rapid growth, despite its TBS problem?

• Is this model sustainable?

• What now needs to be done?

What went wrong – and when did it go wrong?

During the mid-2000s i.e. at time of boom firms abandoned their conservative debt/equity ratios and leveraged themselves up to take advantage of the perceived opportunities, setting off the biggest investment boom financed by an astonishing credit boom in the country’s history, mainly from banks and large inflow of funds from overseas. But just as companies were taking on more risk, things started to go wrong.

• Costs soared far above budgeted levels, as securing land and environmental clearances proved much more difficult and time consuming than expected.

• At the same time, forecast revenues collapsed after the GFC; projects that had been built around the assumption that growth would continue at double-digit levels were suddenly confronted with growth rates half that level.

• Financing cost increased due to RBI increased interest rates to quell double digit inflation.

• For overseas financing rupee depreciated, forcing firms to repay debt at much high exchange rate.

Higher costs, lower revenues, greater financing costs — all squeezed corporate cash flow, quickly leading to debt servicing problems. By 2013, nearly one-third of corporate debt was owed by companies with an interest coverage ratio less than 1 (“IC1 companies”), many of them in the infrastructure (especially power generation) and metals sectors. By 2015, the share of IC1 companies reached nearly 40 percent.

How has India managed to achieve rapid growth, despite its TBS problem? (Twin Balance Sheet Syndrome with Indian Characteristics)

India followed the standard path to the TBS problem: a surge of borrowing, leading to over leverage and debt servicing problems. What distinguished India from other countries was the consequence of TBS. TBS did not lead to economic stagnation in India, as occurred in the U.S. and Europe after the Global Financial Crisis. To the contrary, it co-existed with strong levels of aggregate domestic demand, as reflected in high levels of growth despite very weak exports and moderate, at times high, levels of inflation. This is called as Balance sheet Syndrome with Indian Characteristics. This can be explained by following reasons:

• The unusual structure of its banking system (government backed public sector banks), which ensured there would be no financial crisis.

• As supply side constraints were loosened considerably during the boom, investment in infrastructure keep the pace of growth up even after GFC. In comparison, the US boom was based on housing construction, which proved far less useful after the crisis.

• Apart from it Indian financial system adopted the strategy of “give time to time”, meaning to allow time for the corporate wounds to heal. Thus banks decided to give stressed enterprises more time by postponing loan repayments, restructuring by 2014-15 no less than 6.4 percent of their loans outstanding. They also extended fresh funding to the stressed firms to tide them over until demand recovered

As a result, total stressed assets have far exceeded the headline figure of NPAs. Restructured loans along with unrecognised debt (loans owed by IC1 companies that have not even been recognised as problem debts – the ones that have been “ever greened”, where banks lend firms the money needed to pay their interest obligations) which are estimated at around 4 percent of gross loans, and perhaps 5 percent at public sector banks. In that case, total stressed assets would amount to about 16.6 per cent of banking system loans – and nearly 20 percent of loans at the state banks. Now the question raised is:

Is this Strategy sustainable?

For some years the financing strategy has worked, in the sense that it has allowed India to grow rapidly, despite a significant twin balance sheet problem. But this strategy may now be reaching its limits. After eight years of buying time, there is still no sign that the affected companies are regaining their health, or even that the bad debt problem is being contained.

To the contrary, the stress on corporates and banks is continuing to intensify, and this in turn is taking a measurable toll on investment and credit. Moreover, efforts to offset these trends by providing macroeconomic stimulus are not proving sufficient: the increase in public investment has been more than offset by the fall in private investment, while until demonetisation monetary easing had not been transmitted to bank borrowers because banks had been widening their margins instead. In these circumstances, it has become increasingly clear that the underlying debt problem will finally need to be addressed, lest it derails India’s growth trajectory.

For some years the financing strategy has worked, in the sense that it has allowed India to grow rapidly, despite a significant twin balance sheet problem. But this strategy may now be reaching its limits. After eight years of buying time, there is still no sign that the affected companies are regaining their health, or even that the bad debt problem is being contained.

To the contrary, the stress on corporates and banks is continuing to intensify, and this in turn is taking a measurable toll on investment and credit. Moreover, efforts to offset these trends by providing macroeconomic stimulus are not proving sufficient: the increase in public investment has been more than offset by the fall in private investment, while until demonetisation monetary easing had not been transmitted to bank borrowers because banks had been widening their margins instead. In these circumstances, it has become increasingly clear that the underlying debt problem will finally need to be addressed, lest it derails India’s growth trajectory.

What needs to be done?

In these circumstances, it has become increasingly clear that the underlying debt problem will finally need to be addressed, lest it derails India’s growth trajectory.

• Steps Taken by RBI to deal with the stressed asset problem which include the 5/25 Refinancing of Infrastructure Scheme, Initially, the schemes focused on rescheduling amortisations to give firms more time to repay But as it became apparent that the financial position of the stressed firms was deteriorating, the RBI deployed mechanisms to deal with solvency issues, as well.

• RBI has been encouraging the establishment of private Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs), in the hope that they would buy up the bad loans of the commercial banks. The problem is that ARCs have found it difficult to recover much from the debtors. Thus they have only been able to offer low prices to banks, prices which banks have found it difficult to accept.

• So the RBI has focussed more recently on two other, bank-based workout mechanisms. In June 2015, the Strategic Debt Restructuring (SDR) scheme was introduced, under which creditors could take over firms that were unable to pay and sell them to new owners. The following year, the Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets (S4A) was announced, under which creditors could provide firms with debt reductions up to 50 percent in order to restore their financial viability. The success of these limited by only few number of cases settled under these schemes.

In these circumstances, it has become increasingly clear that the underlying debt problem will finally need to be addressed, lest it derails India’s growth trajectory.

• Steps Taken by RBI to deal with the stressed asset problem which include the 5/25 Refinancing of Infrastructure Scheme, Initially, the schemes focused on rescheduling amortisations to give firms more time to repay But as it became apparent that the financial position of the stressed firms was deteriorating, the RBI deployed mechanisms to deal with solvency issues, as well.

• RBI has been encouraging the establishment of private Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs), in the hope that they would buy up the bad loans of the commercial banks. The problem is that ARCs have found it difficult to recover much from the debtors. Thus they have only been able to offer low prices to banks, prices which banks have found it difficult to accept.

• So the RBI has focussed more recently on two other, bank-based workout mechanisms. In June 2015, the Strategic Debt Restructuring (SDR) scheme was introduced, under which creditors could take over firms that were unable to pay and sell them to new owners. The following year, the Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets (S4A) was announced, under which creditors could provide firms with debt reductions up to 50 percent in order to restore their financial viability. The success of these limited by only few number of cases settled under these schemes.

Reasons Why Schemes has Limited Success

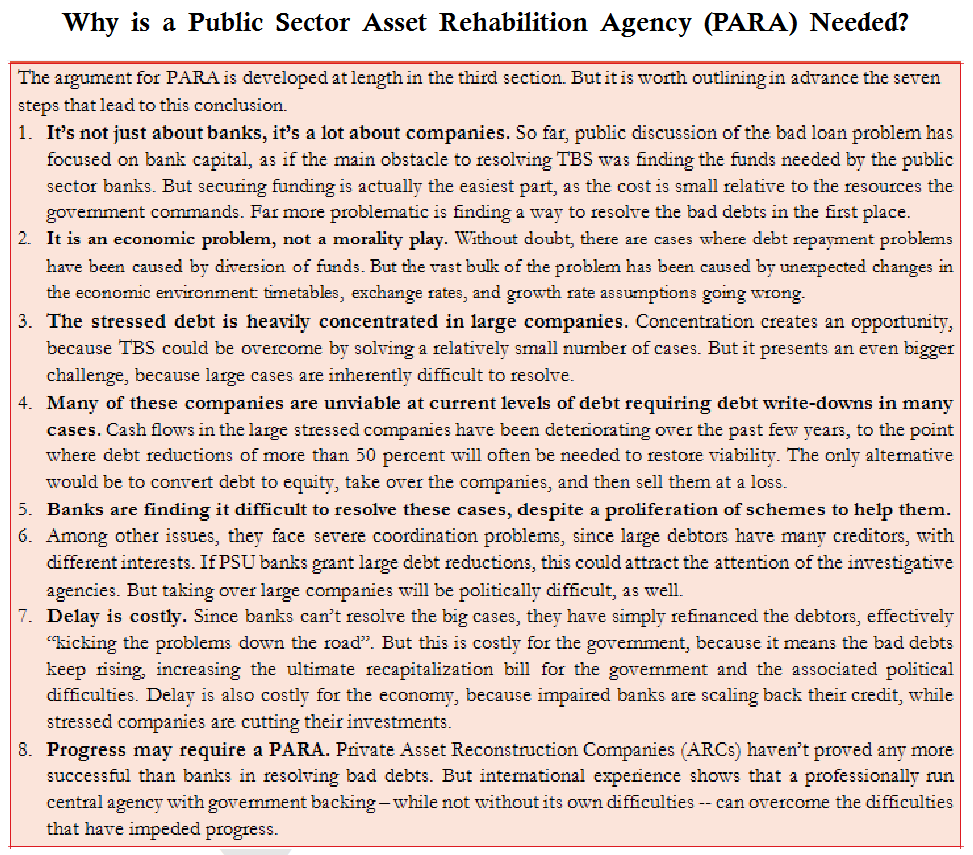

In part, the problem is simply that the schemes are new, and financial restructuring negotiations inevitably take some time. But the bigger problem is that the key elements needed for resolution are still not firmly in place:

• Ever greening of loans increased the unrecognised stress assets.

• Failure of Joint Lenders Forums to arrive on single decision.

• Proper incentives were missing for public sector bankers to grant write down under S4A scheme to restore viability. To the contrary, there is an inherent threat of punishment, since major write-downs can attract the attention of investigative agencies.

• Recapitalisation by government under Indradhanush scheme was limited.

• Stressed assets are concentrated in a remarkably few borrowers, with a mere 50 companies accounting for 71 percent of the debt owed by IC1 debtors. Thus for the big firms the road is not littered with obstacles. It seems to be positively blocked.

All of this suggests that it might not be possible to solve the stressed asset problem using the current mechanism, or indeed any other decentralised approach that might materialise in the near future. Instead a centralised approach might be needed.

One possible strategy would be to create a ‘Public Sector Asset Rehabilitation Agency’ (PARA), charged with working out the largest and most complex cases. Such an approach could eliminate most of the obstacles currently plaguing loan resolution. It could solve the coordination problem, since debts would be centralised in one agency; it could be set up with proper incentives by giving it an explicit mandate to maximize recoveries within a defined time period; and it would separate the loan resolution process from concerns about bank capital.

In part, the problem is simply that the schemes are new, and financial restructuring negotiations inevitably take some time. But the bigger problem is that the key elements needed for resolution are still not firmly in place:

• Ever greening of loans increased the unrecognised stress assets.

• Failure of Joint Lenders Forums to arrive on single decision.

• Proper incentives were missing for public sector bankers to grant write down under S4A scheme to restore viability. To the contrary, there is an inherent threat of punishment, since major write-downs can attract the attention of investigative agencies.

• Recapitalisation by government under Indradhanush scheme was limited.

• Stressed assets are concentrated in a remarkably few borrowers, with a mere 50 companies accounting for 71 percent of the debt owed by IC1 debtors. Thus for the big firms the road is not littered with obstacles. It seems to be positively blocked.

All of this suggests that it might not be possible to solve the stressed asset problem using the current mechanism, or indeed any other decentralised approach that might materialise in the near future. Instead a centralised approach might be needed.

One possible strategy would be to create a ‘Public Sector Asset Rehabilitation Agency’ (PARA), charged with working out the largest and most complex cases. Such an approach could eliminate most of the obstacles currently plaguing loan resolution. It could solve the coordination problem, since debts would be centralised in one agency; it could be set up with proper incentives by giving it an explicit mandate to maximize recoveries within a defined time period; and it would separate the loan resolution process from concerns about bank capital.

How would a PARA Actually Work?

It would purchase specified loans (for example, those belonging to large, over-indebted infrastructure and steel firms) from banks and then work them out, either by converting debt to equity and selling the stakes in auctions or by granting debt reduction, depending on professional assessments of the value-maximizing strategy.

Once the loans are off the books of the public sector banks, the government would recapitalise them, thereby restoring them to financial health and allowing them to shift their resources – financial and human – back toward the critical task of making new loans. For this the capital requirements would nonetheless be large.

• Part would need to come from government issues of securities.

• A second source of funding could be the capital markets, if the PARA were to be structured in a way that would encourage the private sector to take up an equity share.

• A third source of capital could be the RBI. The RBI would (in effect) transfer some of the government securities it is currently holding to public sector banks and PARA. As a result, the RBI’s capital would decrease, while that of the banks and PARA would increase

It would purchase specified loans (for example, those belonging to large, over-indebted infrastructure and steel firms) from banks and then work them out, either by converting debt to equity and selling the stakes in auctions or by granting debt reduction, depending on professional assessments of the value-maximizing strategy.

Once the loans are off the books of the public sector banks, the government would recapitalise them, thereby restoring them to financial health and allowing them to shift their resources – financial and human – back toward the critical task of making new loans. For this the capital requirements would nonetheless be large.

• Part would need to come from government issues of securities.

• A second source of funding could be the capital markets, if the PARA were to be structured in a way that would encourage the private sector to take up an equity share.

• A third source of capital could be the RBI. The RBI would (in effect) transfer some of the government securities it is currently holding to public sector banks and PARA. As a result, the RBI’s capital would decrease, while that of the banks and PARA would increase

Issues Need to Resolve for Proper Functioning of PARA

• First, there needs to be a readiness to confront the losses that have already occurred in the banking system, and accept the political consequences of dealing with the problem.

• Second, the PARA needs to follow commercial rather than political principles.

• The third issue is pricing. To transfer loan to PARA market prices could be used, but establishing the market price of distressed loans is difficult and would prove time consuming.

• First, there needs to be a readiness to confront the losses that have already occurred in the banking system, and accept the political consequences of dealing with the problem.

• Second, the PARA needs to follow commercial rather than political principles.

• The third issue is pricing. To transfer loan to PARA market prices could be used, but establishing the market price of distressed loans is difficult and would prove time consuming.

Conclusion

Addressing the stressed assets problem would require 4 R’s: Reform, Recognition, Recapitalization, and Resolution. This is the second time in a decade that such a large share of their portfolios has turned nonperforming – unless there are fundamental reforms, the problem will recur again and again. Following the RBI’s Asset Quality Review, banks have recognised a growing number of loans as non-performing. With higher NPAs has come higher provisioning, which has eaten into banks’ capital base. As a result, banks will need to be recapitalised – the third R — much of which will need to be funded by the government, at least for the public sector banks. The key issue is the fourth R: Resolution. For even if the public sector banks are recapitalised, they are unlikely to increase their lending until they truly know the losses they will suffer on their bad loans. Nor will the large stressed borrowers be able to increase their investment until their financial positions have been rectified. Until this happens, economic growth will remain under theat.

Addressing the stressed assets problem would require 4 R’s: Reform, Recognition, Recapitalization, and Resolution. This is the second time in a decade that such a large share of their portfolios has turned nonperforming – unless there are fundamental reforms, the problem will recur again and again. Following the RBI’s Asset Quality Review, banks have recognised a growing number of loans as non-performing. With higher NPAs has come higher provisioning, which has eaten into banks’ capital base. As a result, banks will need to be recapitalised – the third R — much of which will need to be funded by the government, at least for the public sector banks. The key issue is the fourth R: Resolution. For even if the public sector banks are recapitalised, they are unlikely to increase their lending until they truly know the losses they will suffer on their bad loans. Nor will the large stressed borrowers be able to increase their investment until their financial positions have been rectified. Until this happens, economic growth will remain under theat.

Supplementary Readings

A. Steps taken by RBI to handle NPA

• The 5/25 Refinancing of Infrastructure Scheme: This scheme offered a larger window for revival of stressed assets in the infrastructure sectors and eight core industry sectors. Under this scheme lenders were allowed to extend amortisation periods to 25 years with interest rates adjusted every 5 years, so as to match the funding period with the long gestation and productive life of these projects.

• Strategic Debt Restructuring (SDR): The RBI came up with the SDR scheme in June 2015 to provide an opportunity to banks to convert debt of companies (whose stressed assets were restructured but which could not finally fulfil the conditions attached to such restructuring) to 51 percent equity and sell them to the highest bidders, subject to authorization by existing shareholders. An 18-month period was envisaged for these transactions, during which the loans could be classified as performing. But as of end-December 2016, only two sales had materialized, in part because many firms remained financially unviable, since only a small portion of their debt had been converted to equity.

• Asset Quality Review (AQR): Resolution of the problem of bad assets requires sound recognition of such assets. Therefore, the RBI emphasized AQR, to verify that banks were assessing loans in line with RBI loan classification rules. Any deviations from such rules were to be rectified by March 2016.

• Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets (S4A): Under this arrangement, introduced in June 2016, an independent agency hired by the banks will decide on how much of the stressed debt of a company is ‘sustainable’. The rest (‘unsustainable’) will be converted into equity and preference shares. Unlike the SDR arrangement, this involves no change in the ownership of the company.

B. Mission Indradhanush – public sector banks’ revamp plan

The seven shades of Indradhanush mission include:

• Appointments: The Government decided to separate the post of Chairman and Managing Director by prescribing that in the subsequent vacancies to be filled up the CEO will get the designation of MD & CEO and there would be another person who would be appointed as non-Executive Chairman of PSBs. This approach is based on global best practices and as per the guidelines in the Companies Act to ensure appropriate checks and balances. The selection process for both these positions has been transparent and meritocratic. The entire process of selection for MD & CEO was revamped. Private sector candidates were also allowed to apply for the position of MD & CEO.

• Bank Board Bureau: The BBB is a body of eminent professionals and officials, which will replace the Appointments Board for appointment of Whole-time Directors as well as non-Executive Chairman of PSBs. They will also constantly engage with the Board of Directors of all the PSBs to formulate appropriate strategies for their growth and development.

• Capitalization: As of now, the PSBs are adequately capitalized and meeting all the Basel III and RBI norms. However, the Government of India wants to adequately capitalize all the banks to keep a safe buffer over and above the minimum norms of Basel III. The capital requirement of extra capital for years up to FY 2019 is likely to be about Rs.1,80,000 crores. Out of the total requirement, the Government of India proposes to make available Rs.70,000 crores.

• De-stressing PSBs – The infrastructure sector and core sector have been the major recipient of PSBs’ funding during the past decades. But due to several factors, projects are increasingly stalled/stressed thus leading to NPA burden on banks. Government is addressing problems causing stress in the power, steel and road sectors which would improve operations in these sectors and consequently De-stress PSB’s

• Strengthening Risk Control measures and NPA Disclosures : Besides the recovery efforts under the DRT & SARFASI mechanism the following additional steps have been taken to address the issue of NPAs:

a) Creation of a Central Repository of Information on Large Credits (CRILC) by RBI

b) Formation of Joint Lenders Forum (JLF), Corrective Action Plan (CAP), and sale of assets. – The Framework outlines formation of JLF and corrective action plan that will incentivise early identification of problem cases, timely restructuring of accounts which are considered to be viable, and taking prompt steps by banks for recovery or sale of unviable accounts.

c) Establishment of six New DRTs

d) Flexible Structuring of Loan Term Project Loans to Infrastructure and Core Industries

• Empowerment: The Government has issued a circular that there will be no interference from Government and Banks are encouraged to take their decision independently keeping the commercial interest of the organisation in mind.

• Framework of Accountability: A new framework of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to be measured for performance of PSBs is being announced. It is divided into four sections relating to efficiency of capital use, diversification of business/processes, NPA management and financial inclusion.

• Governance Reforms: Banks have been assured of “no interference policy”, but at the same time asking them to have robust grievance redressal mechanism for borrowers, depositors as well as staff.

A. Steps taken by RBI to handle NPA

• The 5/25 Refinancing of Infrastructure Scheme: This scheme offered a larger window for revival of stressed assets in the infrastructure sectors and eight core industry sectors. Under this scheme lenders were allowed to extend amortisation periods to 25 years with interest rates adjusted every 5 years, so as to match the funding period with the long gestation and productive life of these projects.

• Strategic Debt Restructuring (SDR): The RBI came up with the SDR scheme in June 2015 to provide an opportunity to banks to convert debt of companies (whose stressed assets were restructured but which could not finally fulfil the conditions attached to such restructuring) to 51 percent equity and sell them to the highest bidders, subject to authorization by existing shareholders. An 18-month period was envisaged for these transactions, during which the loans could be classified as performing. But as of end-December 2016, only two sales had materialized, in part because many firms remained financially unviable, since only a small portion of their debt had been converted to equity.

• Asset Quality Review (AQR): Resolution of the problem of bad assets requires sound recognition of such assets. Therefore, the RBI emphasized AQR, to verify that banks were assessing loans in line with RBI loan classification rules. Any deviations from such rules were to be rectified by March 2016.

• Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets (S4A): Under this arrangement, introduced in June 2016, an independent agency hired by the banks will decide on how much of the stressed debt of a company is ‘sustainable’. The rest (‘unsustainable’) will be converted into equity and preference shares. Unlike the SDR arrangement, this involves no change in the ownership of the company.

B. Mission Indradhanush – public sector banks’ revamp plan

The seven shades of Indradhanush mission include:

• Appointments: The Government decided to separate the post of Chairman and Managing Director by prescribing that in the subsequent vacancies to be filled up the CEO will get the designation of MD & CEO and there would be another person who would be appointed as non-Executive Chairman of PSBs. This approach is based on global best practices and as per the guidelines in the Companies Act to ensure appropriate checks and balances. The selection process for both these positions has been transparent and meritocratic. The entire process of selection for MD & CEO was revamped. Private sector candidates were also allowed to apply for the position of MD & CEO.

• Bank Board Bureau: The BBB is a body of eminent professionals and officials, which will replace the Appointments Board for appointment of Whole-time Directors as well as non-Executive Chairman of PSBs. They will also constantly engage with the Board of Directors of all the PSBs to formulate appropriate strategies for their growth and development.

• Capitalization: As of now, the PSBs are adequately capitalized and meeting all the Basel III and RBI norms. However, the Government of India wants to adequately capitalize all the banks to keep a safe buffer over and above the minimum norms of Basel III. The capital requirement of extra capital for years up to FY 2019 is likely to be about Rs.1,80,000 crores. Out of the total requirement, the Government of India proposes to make available Rs.70,000 crores.

• De-stressing PSBs – The infrastructure sector and core sector have been the major recipient of PSBs’ funding during the past decades. But due to several factors, projects are increasingly stalled/stressed thus leading to NPA burden on banks. Government is addressing problems causing stress in the power, steel and road sectors which would improve operations in these sectors and consequently De-stress PSB’s

• Strengthening Risk Control measures and NPA Disclosures : Besides the recovery efforts under the DRT & SARFASI mechanism the following additional steps have been taken to address the issue of NPAs:

a) Creation of a Central Repository of Information on Large Credits (CRILC) by RBI

b) Formation of Joint Lenders Forum (JLF), Corrective Action Plan (CAP), and sale of assets. – The Framework outlines formation of JLF and corrective action plan that will incentivise early identification of problem cases, timely restructuring of accounts which are considered to be viable, and taking prompt steps by banks for recovery or sale of unviable accounts.

c) Establishment of six New DRTs

d) Flexible Structuring of Loan Term Project Loans to Infrastructure and Core Industries

• Empowerment: The Government has issued a circular that there will be no interference from Government and Banks are encouraged to take their decision independently keeping the commercial interest of the organisation in mind.

• Framework of Accountability: A new framework of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to be measured for performance of PSBs is being announced. It is divided into four sections relating to efficiency of capital use, diversification of business/processes, NPA management and financial inclusion.

• Governance Reforms: Banks have been assured of “no interference policy”, but at the same time asking them to have robust grievance redressal mechanism for borrowers, depositors as well as staff.

DTAA

DTAA

It stands for Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement. A DTAA is a tax treaty signed between two or more countries. Its key objective is that tax-payers in these countries can avoid being taxed twice for the same income. A DTAA applies in cases where a tax-payer resides in one country and earns income in another. DTAAs can either be comprehensive to cover all sources of income or be limited to certain areas such as taxing of income from shipping, air transport, inheritance, etc.

India has DTAAs with which nations?

India has DTAAs with more than eighty countries, of which comprehensive agreements include those with Australia, Canada, Germany, Mauritius, Singapore, UAE, UK and USA.

India has DTAAs with more than eighty countries, of which comprehensive agreements include those with Australia, Canada, Germany, Mauritius, Singapore, UAE, UK and USA.

What are the benefits of DTAA?

DTAAs are intended to make a country an attractive investment destination by providing relief on dual taxation. Such relief is provided by exempting income earned abroad from tax in the resident country or providing credit to the extent taxes have already been paid abroad.

For example, if a person is sent on deputation abroad and receive emoluments during stint away from home, income may sometimes be subject to tax in both the countries. The person can claim relief when filing tax return for that financial year, if there is an applicable DTAA. Similarly, if the person is an NRI having investments in India, DTAA provisions may also be applicable to income from these investments or from their sale.

DTAAs also provide for concessional rates of tax in some cases. For instance, interest on NRI bank deposits attract 30 per cent TDS (tax deduction at source) here. But under the DTAAs that India has signed with several countries, tax is deducted at only 10 to 15 per cent. Many of India’s DTAAs also have lower tax rates for royalty, fee for technical services, etc.

Example citing the working of DTAA:

An NRI individual living in X country maintains an NRO account with a bank based in India. The interest income on the balance amount in the NRO account is deemed as income that originates in India and hence is taxable in India.

In case, India and X nation are contracted under the DTAA, this income will have tax implications in accordance with the rate specified in the agreement. Otherwise, the interest income will attract tax @ 30.90 % i.e. the current withholding tax. Also, NRI is entitled to avail the benefits under the provisions of DTAA between India and his country of residence with respect to interest income on government securities, company fixed deposits, dividend and loans.

Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement

Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement

• The MCAA is a multilateral framework agreement that provides a standardised and efficient mechanism to facilitate the Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) in accordance with the Standard for Automatic Exchange of Financial Information in Tax Matters (“the Standard”).

• It avoids the need for several bilateral agreements to be concluded.

• AEOI based on CRS (Common Reporting Standards)

• It always ensures each signatory has ultimate control over exactly which exchange relationships it enters into and that each signatory’s standards on confidentiality and data protection always apply.

• India joined MCAA on 3rd June, 2015, in Paris. India to receive information from almost every country in the world including offshore financial centres.

• It would be instrumental in getting information about assets of Indians held abroad including through entities in which Indians are beneficial owners

• For implementation, necessary legislative changes have been made by amending Income-tax Act, 1961.

• It is a key to prevent international tax evasion and avoidance.

• It avoids the need for several bilateral agreements to be concluded.

• AEOI based on CRS (Common Reporting Standards)

• It always ensures each signatory has ultimate control over exactly which exchange relationships it enters into and that each signatory’s standards on confidentiality and data protection always apply.

• India joined MCAA on 3rd June, 2015, in Paris. India to receive information from almost every country in the world including offshore financial centres.

• It would be instrumental in getting information about assets of Indians held abroad including through entities in which Indians are beneficial owners

• For implementation, necessary legislative changes have been made by amending Income-tax Act, 1961.

• It is a key to prevent international tax evasion and avoidance.

Financial Stability and Development Council (FSDC)

Financial Stability and Development Council (FSDC)

It is an apex-level body constituted by the government of India.

Recommendations for such a super regulatory body were first mooted by the Raghuram Rajan Committee in 2008. Finally in 2010, the then Finance Minister of India, Pranab Mukherjee, decided to set up such an autonomous body dealing with macro prudential and financial regularities in the entire financial sector of India.

FSDC has replaced the High Level Coordination Committee on Financial Markets (HLCCFM), which was facilitating regulatory coordination, though informally, prior to the setting up of FSDC. It is not a statutory body.

Chairperson: The Union Finance Minister of India

Members: Heads of the financial sector regulatory authorities (i.e., RBI, SEBI, IRDA, and PFRDA), Finance Secretary and/or Secretary, Department of Economic Affairs (Union Finance Ministry), Secretary, Department of Financial Services, and Chief Economic Adviser. FSDC can invite experts to its meeting if required.

The objectives of FSDC would be to deal with issues relating to:

• Financial stability

• Financial sector development

• Inter-regulatory coordination

• Financial literacy

• Financial inclusion

• Macro prudential supervision of the economy including the functioning of large financial conglomerates.

• Coordinating India’s international interface with financial sector bodies such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and Financial Stability Board (FSB).

• Financial sector development

• Inter-regulatory coordination

• Financial literacy

• Financial inclusion

• Macro prudential supervision of the economy including the functioning of large financial conglomerates.

• Coordinating India’s international interface with financial sector bodies such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and Financial Stability Board (FSB).

Functions: To strengthen and institutionalise the mechanism of maintaining financial stability, Financial Literacy, Financial Inclusion, financial sector development, inter-regulatory coordination along with monitoring macro-prudential regulation of economy. FSDC was formed to bring greater coordination among financial market regulators.

The FSDC Sub Committee Chaired by the Governor of the RBI. All the members of the FSDC are also the members of the Sub-committee. Additionally, all four Deputy Governors of the RBI and Additional Secretary, DEA, in charge of FSDC, are also members of the Sub Committee. The Council/Sub-committee deliberates on these issues and suggests taking appropriate steps, as required.

FSDC was formed to bring greater coordination among financial market regulators. The council is headed by the finance minister and has the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor and chairpersons of the Securities and Exchange Board of India, Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority and Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority as other members along with finance ministry officials.

No comments:

Post a Comment