External Sector

External Sector

External Sector

• The external sector of the economy refers to the international transactions that both the private and public sector conduct with the rest of the world. Such transactions are systematically recorded in detail within a framework that groups them into accounts, where each account represents a separate economic process or phenomenon of the external sector.

• The external accounts form part of an integrated system of statistics of the economy, and thus all definitions, classifications and accounting rules must be harmonized so that external sector aggregates can be compared and summed with other macroeconomic data, such as those of national accounts, monetary statistics and government statistics. In the goods market, the external sector involves exports and imports. In the financial market it involves capital flows.

• Economic features related to the external sector are as follows:

A. Forex Reserves

• Foreign-exchange reserves or Forex reserves is money or other assets held by a central bank or other monetary authority so that it can pay if need be its liabilities, such as the currency issued by the central bank, as well as the various bank reserves deposited with the central bank by the government and other financial institutions.

• Reserves are held in mostly the United States dollar and to a lesser extent the EU’s Euro, the British Pound sterling, and the Japanese Yen.

• In a strict sense, foreign-exchange reserves should only include foreign banknotes, foreign bank deposits, foreign treasury bills, and short and long-term foreign government securities. However, the term in popular usage commonly also adds gold reserves, special drawing rights (SDRs), and International Monetary Fund (IMF) reserve positions.

• Foreign-exchange reserves are called reserve assets in the balance of payments and are located in the capital account.

B. External Debt

• It is that portion of a country’s debt that was borrowed from foreign lenders including commercial banks, governments or international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank.

B. External Debt

• It is that portion of a country’s debt that was borrowed from foreign lenders including commercial banks, governments or international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank.

• According to the IMF, “Gross external debt is the amount, at any given time, of disbursed and outstanding contractual liabilities of residents of a country to nonresidents to repay principal, with or without interest, or to pay interest, with or without principal”.

• Sustainable debt is the level of debt which allows a debtor country to meet its current and future debt service obligations in full, without recourse to further debt relief or rescheduling, avoiding accumulation of arrears, while allowing an acceptable level of economic growth.

• There are various indicators for determining a sustainable level of external debt. These indicators can be thought of as measures of the country’s solvency. Examples of debt burden indicators include the external debt-to-GDP ratio, external debt-to-total debt ratio etc.

C. Balance of Payment

• Balance of Payment is a systematic record of all the transactions that a nation carries out with outside world. It is the difference between what a nation gets from outside world and what it pays to the outside world. Balance of Payment (BoP) comprises current account, capital account, errors, omissions, changes in foreign exchange reserves.

C. Balance of Payment

• Balance of Payment is a systematic record of all the transactions that a nation carries out with outside world. It is the difference between what a nation gets from outside world and what it pays to the outside world. Balance of Payment (BoP) comprises current account, capital account, errors, omissions, changes in foreign exchange reserves.

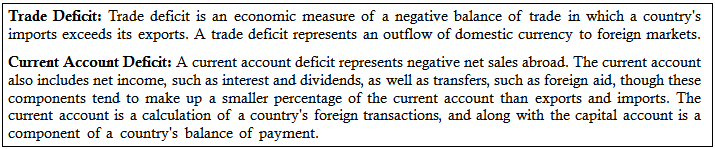

• Current Account – Under current account of the BoP, transactions are classified into merchandise goods (exports and imports) and invisibles. Invisible transactions are further classified into three categories, namely

a) Services – travel, transportation, insurance, Government not included elsewhere (GNIE) and miscellaneous (such as, communication, construction, financial, software, news agency, royalties, management and business services),

b) Income, and

c) Transfers (grants, gifts, remittances, etc. which do not have any quid pro quo

a) Services – travel, transportation, insurance, Government not included elsewhere (GNIE) and miscellaneous (such as, communication, construction, financial, software, news agency, royalties, management and business services),

b) Income, and

c) Transfers (grants, gifts, remittances, etc. which do not have any quid pro quo

• Capital Account – Under capital account, capital inflows can be classified by instrument (debt or equity) and maturity (short or long-term). The main components of capital account include foreign investment, loans and banking capital.

• Foreign investment comprising Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and portfolio investment consisting of Foreign Institutional Investors (FIIs) investment, American Depository Receipts/Global Depository Receipts (ADRs/GDRs) represents non-debt liabilities, while loans (external assistance, external commercial borrowings and trade credit) and banking capital including non-resident Indian (NRI) deposits are debt liabilities.

D. Foreign investment – It comprises of two components:

1) Foreign Direct Investment – FDI is foreign investment with aim of profit motive and provide unique mixture of resources, technology, knowledge, professionalism and management techniques.

• India’s economy has been opening for more FDI. 100% FDI is permitted in sectors like petroleum sector, road building, power, drugs and pharmaceuticals hotels and tourism.

• No FDI is allowed in gambling, betting, lottery, atomic energy etc.

• FDI in India is allowed under Automatic Route i.e. without prior approval of government/RBI whereas other is government route which requires approval of FIPB.

D. Foreign investment – It comprises of two components:

1) Foreign Direct Investment – FDI is foreign investment with aim of profit motive and provide unique mixture of resources, technology, knowledge, professionalism and management techniques.

• India’s economy has been opening for more FDI. 100% FDI is permitted in sectors like petroleum sector, road building, power, drugs and pharmaceuticals hotels and tourism.

• No FDI is allowed in gambling, betting, lottery, atomic energy etc.

• FDI in India is allowed under Automatic Route i.e. without prior approval of government/RBI whereas other is government route which requires approval of FIPB.

2) Foreign Institutional Investment – FII or Foreign institutional Investment is done in the stock market with the purpose of only trading in shares of companies, in corporate debt and in government securities. Such investments are volatile in nature.

• There is no restriction on FII in the stock market except for the maximum percent shares of a company including in corporate debt instruments and government securities.

• FII also comes in the form of participatory notes (PN) (unregistered FII) and round tipping. Through round tipping, capital goes out of the country only to return from a different route to avoid incidence of tax on profit earned. Much of FII invested in India comes from Mauritius taking advantage of Double Taxation Avoidance Treaty.

• Balance of payment of a country is a separate and independent “record” of all transactions being done in foreign currency in the country. It has great significance for open economies.

• FII also comes in the form of participatory notes (PN) (unregistered FII) and round tipping. Through round tipping, capital goes out of the country only to return from a different route to avoid incidence of tax on profit earned. Much of FII invested in India comes from Mauritius taking advantage of Double Taxation Avoidance Treaty.

• Balance of payment of a country is a separate and independent “record” of all transactions being done in foreign currency in the country. It has great significance for open economies.

E. Exchange Rate – Exchange rate is the value for domestic currency with respect to foreign currency and vice-versa. In India, exchange rates are managed and any capital inflows would be mopped up by RBI to prevent rupee from appreciating thus resulting in build of reserves. They can be either fixed exchange rate or market determined exchange rates.

1) Fixed Exchange Rate System – They are arrived at the intervention of the Central Bank. There are two types of such interventions.

• Currency Board System

– It is done in inflated economies.

– The central bank pegs the home currency to a stronger currency on a 1:1 basis or some different but fixed ratio.

– Home currency will be in circulation equal to inflowing foreign currency.

– Example: Argentina

– It is done in inflated economies.

– The central bank pegs the home currency to a stronger currency on a 1:1 basis or some different but fixed ratio.

– Home currency will be in circulation equal to inflowing foreign currency.

– Example: Argentina

• Crawling pegged exchange rate

– Fixed rate but Central Bank allows it float between ceiling and floor rates.

– Example: Russia and China

– Example: Russia and China

2) Flexible exchange Rate system – They are arrived at the intervention of the market. There are two types of such interventions.

• Full float

– Determined by forces of demand and supply of foreign currency in the home country

– No role of Central Bank.

– Examples are USA, EU.

– Market determined rates are seen as maturity of economics and a test for globally competitive economy.

– No role of Central Bank.

– Examples are USA, EU.

– Market determined rates are seen as maturity of economics and a test for globally competitive economy.

• Managed exchange rate – Also referred as “dirty floating” as central bank intrude indirectly in influencing exchange rate.

– In managed exchange rate, even though the exchange rate is market determined, there is active indirect intervention by the central bank to bring exchange rate closer to its own perception.

– Example: India

– If exchange rate is market determined and currency make sizeable portion in terms of trade volume, it is known as hard currency. Examples are USA, Japan and UK, etc.

3) Nominal Effective Exchange Rate and Real Effective Exchange Rate

• The nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) and real effective exchange rate (REER) indices are used as indicators of external competitiveness of the country over a period of time.

– Example: India

– If exchange rate is market determined and currency make sizeable portion in terms of trade volume, it is known as hard currency. Examples are USA, Japan and UK, etc.

3) Nominal Effective Exchange Rate and Real Effective Exchange Rate

• The nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) and real effective exchange rate (REER) indices are used as indicators of external competitiveness of the country over a period of time.

• NEER is the weighted average of bilateral nominal exchange rates of the home currency in terms of foreign currencies, while REER is defined as a weighted average of nominal exchange rates, adjusted for home and foreign country relative price differentials.

• REER captures movements in cross-currency exchange rates as well as inflation differentials between India and its major trading partners and reflects the degree of external competitiveness of Indian products.

• The RBI has been constructing six currency (US Dollar, Euro for Eurozone, Pound Sterling, Japanese Yen, Chinese Renminbi and Hong Kong Dollar) and 36 currency indices of NEER and REER.

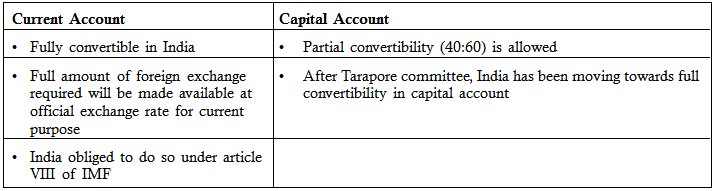

F. Convertibility of Rupee

• An economy allows its currency fully or partially convertibility in its current and capital account. The issue of currency convertibility is concerned with foreign currency outflow.

F. Convertibility of Rupee

• An economy allows its currency fully or partially convertibility in its current and capital account. The issue of currency convertibility is concerned with foreign currency outflow.

• India took different measures to check the foreign exchange outflow in both current and capital account. But with economic reforms, situation changed drastically.

Economic Survey Chapter – 11

One Economic India: For Goods and in the Eyes of the Constitution

One Economic India: For Goods and in the Eyes of the Constitution-Economic Survey Chapter – 11

Context

The popular impression is one of an India having achieved political integration but an incommensurate economic integration. Based on a novel source of Big Data-invoice level transactions from the Goods and Services Tax Network (GSTN)-the chapter documents high levels of internal trade in goods. India’s internal trade-GDP ratio at about 54 per cent is comparable to that in other large countries.

There is enormous variation across states in their internal trade patterns. Smaller states tend to trade more, while the manufacturing states of Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Gujarat tend to have trade surpluses (exporting more than importing). Belying their status as agricultural and/or less developed, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh appear to be manufacturing powerhouses because of their proximity to NCR.

The analysis does leave open the possibility that some proportion of India’s internal trade could be a consequence of current tax distortions, which are likely to be normalised under the GST. One market and greater tax policy integration but less actual trade is an intriguing future prospect.

This chapter is organized as follows.

In Section 1, the findings on Trade are documented and Section 2 examines the Constitutional provisions on promoting internal integration by comparing it with other models. The extent to which the Constitutional provisions facilitate the creation of one economic India is discussed in a final section. The open question is whether laws can more proactively facilitate the economic integration of India or not.

The popular impression is one of an India having achieved political integration but an incommensurate economic integration. Based on a novel source of Big Data-invoice level transactions from the Goods and Services Tax Network (GSTN)-the chapter documents high levels of internal trade in goods. India’s internal trade-GDP ratio at about 54 per cent is comparable to that in other large countries.

There is enormous variation across states in their internal trade patterns. Smaller states tend to trade more, while the manufacturing states of Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Gujarat tend to have trade surpluses (exporting more than importing). Belying their status as agricultural and/or less developed, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh appear to be manufacturing powerhouses because of their proximity to NCR.

The analysis does leave open the possibility that some proportion of India’s internal trade could be a consequence of current tax distortions, which are likely to be normalised under the GST. One market and greater tax policy integration but less actual trade is an intriguing future prospect.

This chapter is organized as follows.

In Section 1, the findings on Trade are documented and Section 2 examines the Constitutional provisions on promoting internal integration by comparing it with other models. The extent to which the Constitutional provisions facilitate the creation of one economic India is discussed in a final section. The open question is whether laws can more proactively facilitate the economic integration of India or not.

Technical Terms

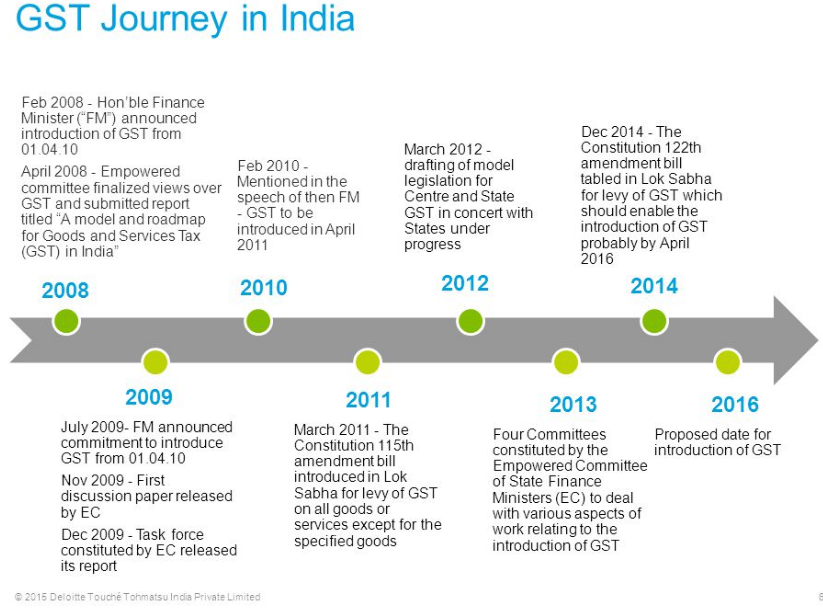

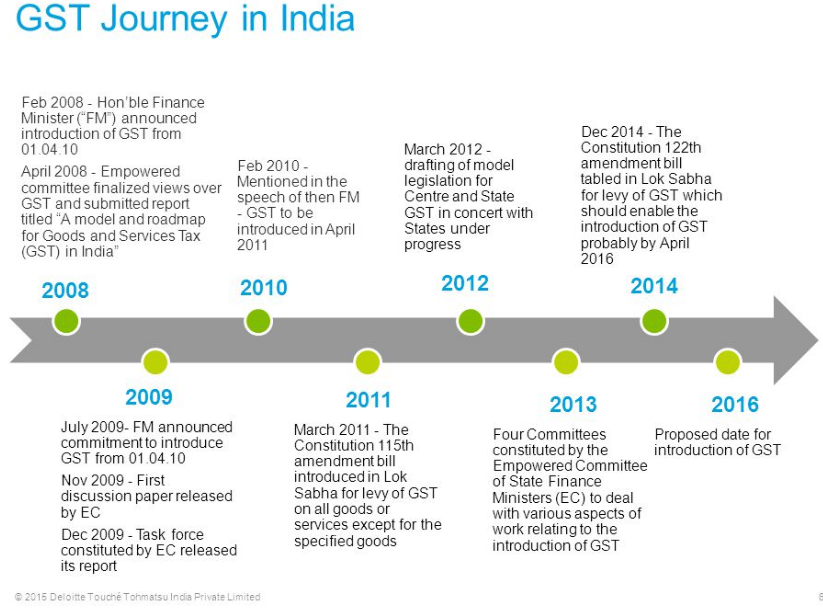

A. Goods and Services Tax (GST) refers to the single unified tax created by amalgamating a large number of Central and State taxes presently applicable in India. The latest constitution Amendment Bill of December 2014 made in this regard, proposes to insert a definition of GST in Article 366 of the constitution by inserting a sub-clause 12A. As per that, GST means any tax on supply of goods, or services, or both, except taxes on supply of the alcoholic liquor for human consumption. And here, services are defined to mean anything other than goods.

GST is a single tax on the supply of goods and services, right from the manufacturer to the consumer. Credits of input taxes paid at each stage will be available in the subsequent stage of value addition, which makes GST essentially a tax only on value addition at each stage. The final consumer will thus bear only the GST charged by the last dealer in the supply chain, with set-off benefits at all the previous stages.

GST is a single tax on the supply of goods and services, right from the manufacturer to the consumer. Credits of input taxes paid at each stage will be available in the subsequent stage of value addition, which makes GST essentially a tax only on value addition at each stage. The final consumer will thus bear only the GST charged by the last dealer in the supply chain, with set-off benefits at all the previous stages.

B. The Central Sales Tax (CST) is a levy of tax on sales, which are effected in the course of inter-State trade or commerce. According to the Constitution of India, no State can levy sales tax on any sales or purchase of goods that takes place in the course of interstate trade or commerce. Only parliament can levy tax on such transaction. The Central Sales Tax Act was enacted in 1956 to formulate principles for determining when a sale or purchase of goods takes place in the course of interstate trade or commerce. The Act also provides for the levy and collection of taxes on sale of goods in the course of interstate trade and commerce and to declare certain goods to be of special importance in the interstate commerce or trade.

The central sales tax is an indirect tax on consumers. Though CST is a central levy, however it is administered by the concerned State in which the sale originates. The seller or a dealer of goods in a State has to collect State Sales Tax on the sale of goods within the State as well as central Sales Tax on sales that takes place in the course interstate trade or commerce.

The central sales tax is an indirect tax on consumers. Though CST is a central levy, however it is administered by the concerned State in which the sale originates. The seller or a dealer of goods in a State has to collect State Sales Tax on the sale of goods within the State as well as central Sales Tax on sales that takes place in the course interstate trade or commerce.

C. Value Added Tax (VAT) is a kind of tax levied on sale of goods and services when these commodities are ultimately sold to the consumer. VAT is an integral part of the GDP of any country. While VAT is levied on sale of goods and services and paid by producers to the government, the actual tax is levied from customers or end users who purchase these. Thus, it is an indirect form of tax which is paid to the government by customers but via producers of goods and services.

VAT is a multi-stage tax which is levied at each step of production of goods and services which involves sale/purchase. Any person earning an annual turnover of more than Rs.5 lacs by supplying goods and services is liable to register for VAT payment. Value added tax or VAT is levied both on local as well as imported goods.

VAT is a multi-stage tax which is levied at each step of production of goods and services which involves sale/purchase. Any person earning an annual turnover of more than Rs.5 lacs by supplying goods and services is liable to register for VAT payment. Value added tax or VAT is levied both on local as well as imported goods.

D. General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), set of multilateral trade agreements aimed at the abolition of quotas and the reduction of tariff duties among the contracting nations. By the time GATT was replaced by the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, 125 nations were signatories to its agreements, which had become a code of conduct governing 90 percent of world trade.

GATT’s most important principle was that of trade without discrimination, in which each member nation opened its markets equally to every other. As embodied in unconditional most-favoured nation clauses, this meant that once a country and its largest trading partners had agreed to reduce a tariff, that tariff cut was automatically extended to every other GATT member.

GATT’s most important principle was that of trade without discrimination, in which each member nation opened its markets equally to every other. As embodied in unconditional most-favoured nation clauses, this meant that once a country and its largest trading partners had agreed to reduce a tariff, that tariff cut was automatically extended to every other GATT member.

Gist of Economic Survey Chapter

While international barriers to trade have been studied extensively, less attention has been devoted to studying the impact of trading networks and other barriers (political and cultural) to trade within countries. The estimation of these barriers to intra-national trade for India has hitherto been challenging due to the absence of a comprehensive interstate trade dataset. This chapter presents the first estimates of internal trade within India using a novel data source – transactions recorded in the process of Central Sales Tax (CST) collection as provided by Tax Information Exchange System (TINXSYS).

The first-ever estimates for interstate trade ûows indicate that cross-border exchanges between and within firms amount to at least 54 per cent of GDP, implying that interstate trade is 1.7 times larger than international trade. Both figures compare favourably with other jurisdictions: de facto at least, India seems well integrated internally. A more technical analysis confirms this, finding that trade costs reduce trade by roughly the same extent in India as in other countries.

The first-ever estimates for interstate trade ûows indicate that cross-border exchanges between and within firms amount to at least 54 per cent of GDP, implying that interstate trade is 1.7 times larger than international trade. Both figures compare favourably with other jurisdictions: de facto at least, India seems well integrated internally. A more technical analysis confirms this, finding that trade costs reduce trade by roughly the same extent in India as in other countries.

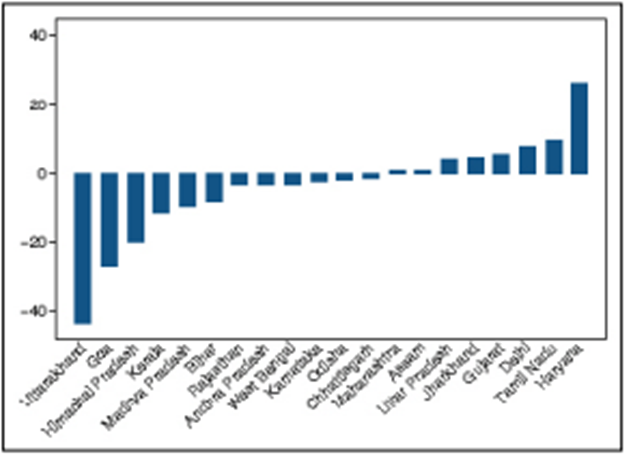

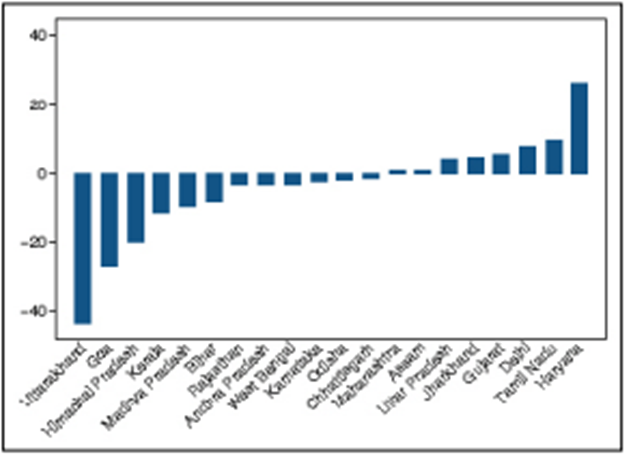

Balance of Interstate Trade: Net Exporters and Net Importers

The large manufacturing states – Gujarat, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu have a positive balance of trade highlighting their competitive manufacturing capabilities. This positive balance is also a feature of Delhi (7.4 per cent), Haryana (26.1 per cent) and UP (4.2 per cent), reûecting the large value additions occurring in the manufacturing hubs of the National Capital Region, namely Gurugram and NOIDA. Gurugram and NOIDA, respectively, make otherwise agricultural Haryana and UP manufacturing powerhouses.

The large manufacturing states – Gujarat, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu have a positive balance of trade highlighting their competitive manufacturing capabilities. This positive balance is also a feature of Delhi (7.4 per cent), Haryana (26.1 per cent) and UP (4.2 per cent), reûecting the large value additions occurring in the manufacturing hubs of the National Capital Region, namely Gurugram and NOIDA. Gurugram and NOIDA, respectively, make otherwise agricultural Haryana and UP manufacturing powerhouses.

Trade Balance (Net Exports as per cent of GSDP)

The CST and VAT

Under the current system, states levy a value-added tax on most goods sold within the state, the centre levies a near VATable excise tax at the production stage. Sales of goods across states fall outside the VAT system and are subjected to an origin-based non-VATable tax (the Central Sales Tax, CST). It turns out that the CST – far from acting as a tariff on interstate trade – may actually provide an arbitrage opportunity away from a higher VAT rate on intra-state sales in some cases.

Contrary to the caricature, India’s internal trade in goods seems surprisingly robust. This is true whether it is compared to India’s external trade, internal trade of other countries, or gravity-based trade patterns in the United States. For example, the effect of distance on trade seems lower in India than in the US. Hearteningly, it seems that language is not a serious barrier to trade. There is enormous variation across states in their internal trade patterns. Smaller states tend to trade more, while the manufacturing states of Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Gujarat tend to have trade surpluses (exporting more than importing). Belying their status as agricultural and/or less developed, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh appear to be manufacturing powerhouses because of their proximity to NCR. The analysis does leave open the possibility that some proportion of India’s internal trade could be a consequence of current tax distortions, which are likely to be normalised under the GST. One market and greater tax policy integration but less actual trade is an intriguing future prospect.

Under the current system, states levy a value-added tax on most goods sold within the state, the centre levies a near VATable excise tax at the production stage. Sales of goods across states fall outside the VAT system and are subjected to an origin-based non-VATable tax (the Central Sales Tax, CST). It turns out that the CST – far from acting as a tariff on interstate trade – may actually provide an arbitrage opportunity away from a higher VAT rate on intra-state sales in some cases.

Contrary to the caricature, India’s internal trade in goods seems surprisingly robust. This is true whether it is compared to India’s external trade, internal trade of other countries, or gravity-based trade patterns in the United States. For example, the effect of distance on trade seems lower in India than in the US. Hearteningly, it seems that language is not a serious barrier to trade. There is enormous variation across states in their internal trade patterns. Smaller states tend to trade more, while the manufacturing states of Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Gujarat tend to have trade surpluses (exporting more than importing). Belying their status as agricultural and/or less developed, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh appear to be manufacturing powerhouses because of their proximity to NCR. The analysis does leave open the possibility that some proportion of India’s internal trade could be a consequence of current tax distortions, which are likely to be normalised under the GST. One market and greater tax policy integration but less actual trade is an intriguing future prospect.

GST

The GST was justly touted as leading to the creation of One Tax, One Market, One India. But it is worth reûecting how far India is from that ideal. Indian states have levied any number of charges on goods that hinder free trade in India—octroi duties, entry taxes, Central Sales Tax (CST) to name a few. The most egregious example of levying charges of services coming from other states is the cross-state power surcharge that raises the cost of manufacturing, fragments the Indian power market and sustains inefficient cross-subsidization of power within states.

In agriculture, Agriculture Produce Market Committee (APMCs) still proliferate which prevent the easy sales of agricultural produce across states, depriving the farmer of better returns and higher incomes, and reducing agricultural productivity in India. These measures in agriculture, goods, and services make light of claims that there is one economic India.

There is an obvious conceptual commonality of public policy objectives in large federations or supra-national entities: balancing the imperative of creating a common market so that all producers and consumers are treated alike, with the imperative of not undermining the legitimate sovereignty of the sub-federal units. Three comparators suggest themselves: other federal countries such as the United States; other federal structures comprising countries such as the European Union; or multilateral trading agreements such as the World Trade Organization (WTO).

The GST was justly touted as leading to the creation of One Tax, One Market, One India. But it is worth reûecting how far India is from that ideal. Indian states have levied any number of charges on goods that hinder free trade in India—octroi duties, entry taxes, Central Sales Tax (CST) to name a few. The most egregious example of levying charges of services coming from other states is the cross-state power surcharge that raises the cost of manufacturing, fragments the Indian power market and sustains inefficient cross-subsidization of power within states.

In agriculture, Agriculture Produce Market Committee (APMCs) still proliferate which prevent the easy sales of agricultural produce across states, depriving the farmer of better returns and higher incomes, and reducing agricultural productivity in India. These measures in agriculture, goods, and services make light of claims that there is one economic India.

There is an obvious conceptual commonality of public policy objectives in large federations or supra-national entities: balancing the imperative of creating a common market so that all producers and consumers are treated alike, with the imperative of not undermining the legitimate sovereignty of the sub-federal units. Three comparators suggest themselves: other federal countries such as the United States; other federal structures comprising countries such as the European Union; or multilateral trading agreements such as the World Trade Organization (WTO).

India’s Constitutional Provisions and Jurisprudence

That comparison requires understanding the constitutional provisions on both achieving and circumscribing the common market. Articles 301-304 provide a layered set of rights and obligations. Article 301 establishes the fundamental principle that India must be a common market:

301. Freedom of trade, commerce and intercourse. Subject to the other provisions of this Part, trade, commerce and intercourse throughout the territory of India shall be free.

Articles 302-304 both qualify and elaborate on that principle. Article 302 gives Parliament the power to restrict free trade between and within states on grounds of public interest.

302. Power of Parliament to impose restrictions on trade, commerce and intercourse. Parliament may by law impose such restrictions on the freedom of trade, commerce or intercourse between one State and another or within any part of the territory of India as may be required in the public interest.

Article 303 (a) then imposes a most-favored nation type obligation on both Parliament and state legislatures; that is no law or regulation by either can favour one state over another.

303. Restrictions on the legislative powers of the Union and of the States with regard to trade and commerce

(1) Notwithstanding anything in Article 302, neither Parliament nor the Legislature of a State shall have power to make any law giving, or authorising the giving of, any preference to one State over another, or making, or authorising the making of, any discrimination between one State and another, by virtue of any entry relating to trade and commerce in any of the Lists in the Seventh Schedule

Article 304 (a) then imposes a national treatment-type obligation on state legislatures (apparently not on Parliament); that is, no taxes can be applied to the goods originating in another state that are also not applied on goods produced within a state. This Article refers only to taxes and not to regulations more broadly.

304. Restrictions on trade, commerce and intercourse among States Notwithstanding anything in Article 301 or Article 303, the Legislature of a State may by law:

That comparison requires understanding the constitutional provisions on both achieving and circumscribing the common market. Articles 301-304 provide a layered set of rights and obligations. Article 301 establishes the fundamental principle that India must be a common market:

301. Freedom of trade, commerce and intercourse. Subject to the other provisions of this Part, trade, commerce and intercourse throughout the territory of India shall be free.

Articles 302-304 both qualify and elaborate on that principle. Article 302 gives Parliament the power to restrict free trade between and within states on grounds of public interest.

302. Power of Parliament to impose restrictions on trade, commerce and intercourse. Parliament may by law impose such restrictions on the freedom of trade, commerce or intercourse between one State and another or within any part of the territory of India as may be required in the public interest.

Article 303 (a) then imposes a most-favored nation type obligation on both Parliament and state legislatures; that is no law or regulation by either can favour one state over another.

303. Restrictions on the legislative powers of the Union and of the States with regard to trade and commerce

(1) Notwithstanding anything in Article 302, neither Parliament nor the Legislature of a State shall have power to make any law giving, or authorising the giving of, any preference to one State over another, or making, or authorising the making of, any discrimination between one State and another, by virtue of any entry relating to trade and commerce in any of the Lists in the Seventh Schedule

Article 304 (a) then imposes a national treatment-type obligation on state legislatures (apparently not on Parliament); that is, no taxes can be applied to the goods originating in another state that are also not applied on goods produced within a state. This Article refers only to taxes and not to regulations more broadly.

304. Restrictions on trade, commerce and intercourse among States Notwithstanding anything in Article 301 or Article 303, the Legislature of a State may by law:

(a) impose on goods imported from other States or the Union territories any tax to which similar goods manufactured or produced in that State are subject, so, however, as not to discriminate between goods so imported and goods so manufactured or produced; and

But then Article 304 (b) allows state legislatures to restrict trade and commerce on grounds of public interest.

But then Article 304 (b) allows state legislatures to restrict trade and commerce on grounds of public interest.

(b) impose such reasonable restrictions on the freedom of trade, commerce or intercourse with or within that State as may be required in the public interest: Provided that no Bill or amendment for the purposes of clause shall be introduced or moved in the Legislature of a State without the previous sanction of the President

Interestingly, this freedom to the states in Article 304 (b) is only different from that provided to Parliament in Article 302 in that states have to impose “reasonable restrictions” whereas Parliament may impose “restrictions.” Of course, states can only impose restrictions in areas that are either on the state or concurrent list.

The gist of these provisions is that both the Centre and the States have considerable freedom to restrict trade and commerce that hinder the creation of one India.

Moreover, the jurisprudence has unsurprisingly come down in favour of even more permissiveness. Evidently, while the purpose of Part XIII was to ensure free trade in the entire territory of India, this is far from how its practical operation has panned out. Financial levies as well as non-financial barriers imposed by the States have become a major impediment to a common market. Levies in the nature of motor vehicles taxes, taxes at the point of entry of goods into specified local areas, sales tax on manufacturers of goods from outside a particular State, have always existed between States. At the same time, many of such levies are constitutionally valid and have been upheld, in principle, by the Supreme Court.

Interestingly, this freedom to the states in Article 304 (b) is only different from that provided to Parliament in Article 302 in that states have to impose “reasonable restrictions” whereas Parliament may impose “restrictions.” Of course, states can only impose restrictions in areas that are either on the state or concurrent list.

The gist of these provisions is that both the Centre and the States have considerable freedom to restrict trade and commerce that hinder the creation of one India.

Moreover, the jurisprudence has unsurprisingly come down in favour of even more permissiveness. Evidently, while the purpose of Part XIII was to ensure free trade in the entire territory of India, this is far from how its practical operation has panned out. Financial levies as well as non-financial barriers imposed by the States have become a major impediment to a common market. Levies in the nature of motor vehicles taxes, taxes at the point of entry of goods into specified local areas, sales tax on manufacturers of goods from outside a particular State, have always existed between States. At the same time, many of such levies are constitutionally valid and have been upheld, in principle, by the Supreme Court.

Provisions In Other Countries

USA

The United States has a very strong interstate commerce clause in the Constitution. Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 vests Congress with the power: “to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.

A combined reading of these provisions makes it apparent that even in a Constitution where residuary powers are reserved to the states (and not the Union, as is the case in India); states are constitutionally barred from regulating interstate trade and commerce as it was felt that such power would fundamentally hamper free trade and movement.

The United States has a very strong interstate commerce clause in the Constitution. Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 vests Congress with the power: “to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.

A combined reading of these provisions makes it apparent that even in a Constitution where residuary powers are reserved to the states (and not the Union, as is the case in India); states are constitutionally barred from regulating interstate trade and commerce as it was felt that such power would fundamentally hamper free trade and movement.

EU

Since the Maastricht Treaty that created the common market in Europe, it is now accepted that countries within the EU must not, except under narrow circumstances, restrict the four freedoms of movement: of goods, services, capital, and people. Now, it could be argued that both the USA and EU are very different from India because of their long and particular histories of nationhood: for example, it could be argued that Indian states are more diverse than states within the US and hence require greater freedom of tax and regulatory manoeuvre. The counter-argument would of course be that the American states were always fiercely jealous of their sovereignty and that the Constitution embodies that. In this view, the strong interstate commerce clause exists despite strong states. It could also be argued, with even less plausibility however, that states within India should have more regulatory freedom than sovereign countries within Europe.

Since the Maastricht Treaty that created the common market in Europe, it is now accepted that countries within the EU must not, except under narrow circumstances, restrict the four freedoms of movement: of goods, services, capital, and people. Now, it could be argued that both the USA and EU are very different from India because of their long and particular histories of nationhood: for example, it could be argued that Indian states are more diverse than states within the US and hence require greater freedom of tax and regulatory manoeuvre. The counter-argument would of course be that the American states were always fiercely jealous of their sovereignty and that the Constitution embodies that. In this view, the strong interstate commerce clause exists despite strong states. It could also be argued, with even less plausibility however, that states within India should have more regulatory freedom than sovereign countries within Europe.

WTO

There is a third and much weaker standard by which Indian rules should be assessed: the WTO. The comparison between WTO rules and the provisions of the Constitution is not inappropriate. That is, it is reasonable to compare the common-market/regulatory freedom balance provided for countries in the WTO with the same provided for states in the Constitution.

But the key difference with the Constitution is the freedom provided to depart from these anti-protectionism requirements. The contrast is really between Articles 302 and 304 (b) of the Constitution and Article XX of the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade (GATT) WTO.

Article XX – General Exceptions Subject to the requirement that such measures are not applied in a manner which would constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination between countries where the same conditions prevail, or a disguised restriction on international trade, nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to prevent the adoption or enforcement by any contracting party of measures:

(a) Necessary to protect public morals;

(b) Necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health;

(c) Relating to the importations or exportations of gold or silver;

(d) necessary to secure compliance with laws or regulations which are not inconsistent with the provisions of this Agreement, including those relating to customs enforcement, the enforcement of monopolies operated under paragraph 4 of Article II and Article XVII, the protection of patents, trademarks and copyrights, and the prevention of deceptive practices;

(e) Relating to the products of prison labour;

(F) Imposed for the protection of national treasures of artistic, historic or archaeological value;

(g) Relating to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources if such measures are made effective in conjunction with restrictions on domestic production or consumption;

(h) Undertaken in pursuance of obligations under any intergovernmental commodity agreement which conforms to criteria submitted to the CONTRACTING PARTIES and not disapproved by them or which is itself so submitted and not so disapproved;

(i) Involving restrictions on exports of domestic materials necessary to ensure essential quantities of such materials to a domestic processing industry during periods when the domestic price of such materials is held below the world price as part of a governmental stabilization plan; Provided that such restrictions shall not operate to increase the exports of or the protection afforded to such domestic industry, and shall not depart from the provisions of this Agreement relating to non-discrimination;

(j) Essential to the acquisition or distribution of products in general or local short supply; Provided that any such measures shall be consistent with the principle that all contracting parties are entitled to an equitable share of the international supply of such products, and that any such measures, which are inconsistent with the other provisions of the Agreement shall be discontinued as soon as the conditions giving rise to them have ceased to exist…

The key point is that in the WTO the departures from a common market across widely varying countries is quite heavily circumscribed whereas similar departures between states within India is easily condoned by the Constitution and consequent constitutional jurisprudence.

At a time when India is embracing cooperative federalism, the question to ponder is this: even if India cannot embrace the strong standards of a common market prevalent in the US and EU, should not the law in India at least aspire to the weak standards of a common international market embraced by countries around the world?

There is a third and much weaker standard by which Indian rules should be assessed: the WTO. The comparison between WTO rules and the provisions of the Constitution is not inappropriate. That is, it is reasonable to compare the common-market/regulatory freedom balance provided for countries in the WTO with the same provided for states in the Constitution.

But the key difference with the Constitution is the freedom provided to depart from these anti-protectionism requirements. The contrast is really between Articles 302 and 304 (b) of the Constitution and Article XX of the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade (GATT) WTO.

Article XX – General Exceptions Subject to the requirement that such measures are not applied in a manner which would constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination between countries where the same conditions prevail, or a disguised restriction on international trade, nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to prevent the adoption or enforcement by any contracting party of measures:

(a) Necessary to protect public morals;

(b) Necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health;

(c) Relating to the importations or exportations of gold or silver;

(d) necessary to secure compliance with laws or regulations which are not inconsistent with the provisions of this Agreement, including those relating to customs enforcement, the enforcement of monopolies operated under paragraph 4 of Article II and Article XVII, the protection of patents, trademarks and copyrights, and the prevention of deceptive practices;

(e) Relating to the products of prison labour;

(F) Imposed for the protection of national treasures of artistic, historic or archaeological value;

(g) Relating to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources if such measures are made effective in conjunction with restrictions on domestic production or consumption;

(h) Undertaken in pursuance of obligations under any intergovernmental commodity agreement which conforms to criteria submitted to the CONTRACTING PARTIES and not disapproved by them or which is itself so submitted and not so disapproved;

(i) Involving restrictions on exports of domestic materials necessary to ensure essential quantities of such materials to a domestic processing industry during periods when the domestic price of such materials is held below the world price as part of a governmental stabilization plan; Provided that such restrictions shall not operate to increase the exports of or the protection afforded to such domestic industry, and shall not depart from the provisions of this Agreement relating to non-discrimination;

(j) Essential to the acquisition or distribution of products in general or local short supply; Provided that any such measures shall be consistent with the principle that all contracting parties are entitled to an equitable share of the international supply of such products, and that any such measures, which are inconsistent with the other provisions of the Agreement shall be discontinued as soon as the conditions giving rise to them have ceased to exist…

The key point is that in the WTO the departures from a common market across widely varying countries is quite heavily circumscribed whereas similar departures between states within India is easily condoned by the Constitution and consequent constitutional jurisprudence.

At a time when India is embracing cooperative federalism, the question to ponder is this: even if India cannot embrace the strong standards of a common market prevalent in the US and EU, should not the law in India at least aspire to the weak standards of a common international market embraced by countries around the world?

Supplementary Readings

A. GST

GST is one indirect tax for the whole nation, which will make India one unified common market.

GST is one indirect tax for the whole nation, which will make India one unified common market.

Why GST has been proposed?

Our Constitution empowers the Central Government to levy excise duty on manufacturing and service tax on the supply of services. Further, it empowers the State Governments to levy sales tax or value added tax (VAT) on the sale of goods. This exclusive division of fiscal powers has led to a multiplicity of indirect taxes in the country. In addition, central sales tax (CST) is levied on inter-State sale of goods by the Central Government, but collected and retained by the exporting States. Further, many States levy an entry tax on the entry of goods in local areas.

This multiplicity of taxes at the State and Central levels has resulted in a complex indirect tax structure in the country that is ridden with hidden costs for the trade and industry.

In order to simplify and rationalize indirect tax structures, Government of India attempted various tax policy reforms at different points of time. A system of VAT on services at the central government level was introduced in 2002. The states collect taxes through state sales tax VAT, introduced in 2005, levied on intrastate trade and the CST on interstate trade. Despite all the various changes the overall taxation system continues to be complex and has various exemptions.

This led to the idea of One nation One Tax and introduction of GST in Indian financial system. This is simply very similar to VAT which is at present applicable in most of the states and can be termed as National level VAT on Goods and Services with only one difference that in this system not only goods but also services are involved and the rate of tax on goods and services are generally the same.

Our Constitution empowers the Central Government to levy excise duty on manufacturing and service tax on the supply of services. Further, it empowers the State Governments to levy sales tax or value added tax (VAT) on the sale of goods. This exclusive division of fiscal powers has led to a multiplicity of indirect taxes in the country. In addition, central sales tax (CST) is levied on inter-State sale of goods by the Central Government, but collected and retained by the exporting States. Further, many States levy an entry tax on the entry of goods in local areas.

This multiplicity of taxes at the State and Central levels has resulted in a complex indirect tax structure in the country that is ridden with hidden costs for the trade and industry.

In order to simplify and rationalize indirect tax structures, Government of India attempted various tax policy reforms at different points of time. A system of VAT on services at the central government level was introduced in 2002. The states collect taxes through state sales tax VAT, introduced in 2005, levied on intrastate trade and the CST on interstate trade. Despite all the various changes the overall taxation system continues to be complex and has various exemptions.

This led to the idea of One nation One Tax and introduction of GST in Indian financial system. This is simply very similar to VAT which is at present applicable in most of the states and can be termed as National level VAT on Goods and Services with only one difference that in this system not only goods but also services are involved and the rate of tax on goods and services are generally the same.

B. Big Data

Big data is a term that describes the large volume of data – both structured and unstructured – that inundates a business on a day-to-day basis. But it’s not the amount of data that’s important. It’s what organizations do with the data that matters. Big data can be analyzed for insights that lead to better decisions and strategic business moves.

Big data analytics is the process of examining large data sets to uncover hidden patterns, unknown correlations, market trends, customer preferences and other useful business information. The analytical findings can lead to more effective marketing, new revenue opportunities, better customer service, improved operational efficiency, competitive advantages over rival organizations and other business benefits.

The primary goal of big data analytics is to help companies make more informed business decisions by enabling data scientists, predictive modelers and other analytics professionals to analyze large volumes of transaction data, as well as other forms of data that may be untapped by conventional business intelligence (BI) programs. That could include Web server logs and Internet clickstream data, social media content and social network activity reports, text from customer emails and survey responses, mobile-phone call detail records and machine data captured by sensors connected to the Internet of Things.

Big data is a term that describes the large volume of data – both structured and unstructured – that inundates a business on a day-to-day basis. But it’s not the amount of data that’s important. It’s what organizations do with the data that matters. Big data can be analyzed for insights that lead to better decisions and strategic business moves.

Big data analytics is the process of examining large data sets to uncover hidden patterns, unknown correlations, market trends, customer preferences and other useful business information. The analytical findings can lead to more effective marketing, new revenue opportunities, better customer service, improved operational efficiency, competitive advantages over rival organizations and other business benefits.

The primary goal of big data analytics is to help companies make more informed business decisions by enabling data scientists, predictive modelers and other analytics professionals to analyze large volumes of transaction data, as well as other forms of data that may be untapped by conventional business intelligence (BI) programs. That could include Web server logs and Internet clickstream data, social media content and social network activity reports, text from customer emails and survey responses, mobile-phone call detail records and machine data captured by sensors connected to the Internet of Things.

C. Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA)

Traders from both developing and developed countries have long pointed to the vast amount of “red tape” that still exists in moving goods across borders, and which poses a particular burden on small and medium-sized enterprises. To address this, WTO Members concluded negotiations on a landmark Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) at their 2013 Bali Ministerial Conference and are now in the process of adopting measures needed to bring the Agreement into effect.

The TFA contains provisions for expediting the movement, release and clearance of goods, including goods in transit. It also sets out measures for effective cooperation between customs and other appropriate authorities on trade facilitation and customs compliance issues. It further contains provisions for technical assistance and capacity building in this area. The Agreement will help improve transparency, increase possibilities to participate in global value chains, and reduce the scope for corruption.

The TFA was the first Agreement concluded at the WTO by all of its Members.

The Trade Facilitation Agreement contains provisions for expediting the movement, release and clearance of goods, including goods in transit. It also sets out measures for effective cooperation between customs and other appropriate authorities on trade facilitation and customs compliance issues. It further contains provisions for technical assistance and capacity building in this area.

Traders from both developing and developed countries have long pointed to the vast amount of “red tape” that still exists in moving goods across borders, and which poses a particular burden on small and medium-sized enterprises. To address this, WTO Members concluded negotiations on a landmark Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) at their 2013 Bali Ministerial Conference and are now in the process of adopting measures needed to bring the Agreement into effect.

The TFA contains provisions for expediting the movement, release and clearance of goods, including goods in transit. It also sets out measures for effective cooperation between customs and other appropriate authorities on trade facilitation and customs compliance issues. It further contains provisions for technical assistance and capacity building in this area. The Agreement will help improve transparency, increase possibilities to participate in global value chains, and reduce the scope for corruption.

The TFA was the first Agreement concluded at the WTO by all of its Members.

The Trade Facilitation Agreement contains provisions for expediting the movement, release and clearance of goods, including goods in transit. It also sets out measures for effective cooperation between customs and other appropriate authorities on trade facilitation and customs compliance issues. It further contains provisions for technical assistance and capacity building in this area.

D. Some of the Major Initiatives Taken by the Government in the Last Couple of Years to Improve ‘Ease of Doing Business’ in India

Passage of Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code: The government has managed to pass the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, thus clearing the last hurdle for making the code into a law. Experts believe that the law would be in place within a year. The new Bankruptcy law is supposed to significantly reduce the average time taken for the insolvency process to complete, which currently is 4.3 years.

Passage of Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code: The government has managed to pass the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, thus clearing the last hurdle for making the code into a law. Experts believe that the law would be in place within a year. The new Bankruptcy law is supposed to significantly reduce the average time taken for the insolvency process to complete, which currently is 4.3 years.

Time for registering companies reduced: The government has made the process for registering a company faster by reducing the time taken from almost 10 days in December 2014 to 5 days in December 2015. This year the government plans to further reduce the time taken to 1-2 days.

Easier processes for incorporation: To make the process of registering and incorporating companies faster, the government has done away with the requirement of reserving a name, and integrated the processes related to allotment of Director Identification Number (DIN), appointment of directors etc in a single form (INC – 29) for incorporation of a company.

Integration of processes through eBiz portal: The eBiz platform of the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP) integrates several processes across (government) departments to make the process of incorporating a company simpler. One can apply for Permanent Account Number (PAN), Tax Deduction Account Number (TAN), EPFO (Employees’ Provident Fund Organization) and ESIC (Employee’s State Insurance Corporation) and incorporation of company through the eBiz portal.

Doing away with requirement for minimum paid up capital: The minimum paid-up share capital requirement was Rs 1 lakh for a private company and Rs 5 lakh for a public company. This requirement has now been done away with for incorporating private as well as public companies in India.

Making tax laws simpler: The government has accepted most of the first set of recommendations of Easwar Committee for simplification of tax laws. The most important of those being exemption to non-residents from mandatorily having a PAN for lower tax deduction at source, hiking the turnover limit for availing presumptive taxation benefits from Rs1 crore to Rs 2 crore, and deferment of Income Computation and Disclosure Standards (ICDS).

Commercial Courts

Commercial Courts

The efficiency of the legal system and the pace at which disputes are resolved by courts are very important factors in deciding the growth of investment and the overall economic and social development of a country. The inefficiency of our justice delivery system is well known and well documented.

Thus the government has set up Commercial Court system to improve the justice delivery mechanism.

The types of disputes which can be covered under it covers commercial disputes arising from ordinary transactions of merchants, bankers, financiers and traders such as those relating to mercantile documents, export and import of merchandise or service, admiralty and maritime law, transactions relating to aircraft, etc., carriage of goods, construction and infrastructure contracts including tenders, agreements relating to immovable property used exclusively in trade and commerce, infringement of Intellectual Property Rights, exploitation of natural resources, insurance, etc. The definition also includes disputes arising out of agreements of franchising, distribution, licensing, management, consultancy, JV, partnership, shareholders, subscription, investment, etc.

The Act provides for a separate set of Commercial Courts to be set up by State Governments at the District level to try suits and claims pertaining to commercial disputes of a value of at least Rs.1 crore and above. In states where the High Court exercises original civil jurisdiction, the High Courts are expected to set up Commercial Divisions to try such commercial disputes. The Act also requires the High Courts to set up Commercial Appellate Divisions within each High Court to hear appeals from the orders of Commercial Courts and Commercial Divisions (“Courts”) and endeavor to dispose of them within 6 months of their filing date. The Act also amends the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (“CPC”) as will be applicable to the Courts, which shall prevail over the existing High Courts Rules and other provisions of the CPC, so as to improve the efficiency and expeditious disposal of commercial cases.

The establishment of commercial courts in India is a stepping stone to bring about reform in the civil justice system. India’s first Commercial Court and Commercial Disputes Resolution Centre was inaugurated at Raipur, Chhattisgarh.

Bureau of India Standards

Bureau of India Standards

The Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) is the national Standards Body of India working under the aegis of Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food & Public Distribution.

It is established by the Bureau of Indian Standards Act, 1986 which came into effect on 23 December 1986.

The Minister in charge of the Ministry or Department having administrative control of the BIS is the ex-officio President of the BIS.

One of the major functions of the Bureau is the formulation, recognition and promotion of the Indian Standards.

As a corporate body, it has 25 members drawn from Central or State Governments, industry, scientific and research institutions, and consumer organisations.

Its headquarters are in New Delhi, with regional offices in Kolkata, Chennai, Mumbai, Chandigarh and Delhi and 20 branch offices.

It also works as WTO-TBT enquiry point for India.

Bureau of Indian Standards Bill, 2016 passed by the Parliament, is a major step forward in ensuring high quality products and services in the country.

If any customer reports about the degraded quality of any certified product at Grievance Cell, BIS HQs, BIS gives redressal to the customer.

BIS is a founder member of International Organisation for Standardization (ISO).

It represents India in the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and the World Standards Service Network (WSSN).

14th Finance Commission

14th Finance Commission

The Union Cabinet chaired by the Prime Minister has today given its approval to Recommendations on Fiscal Deficit Targets and Additional Fiscal Deficit to States during Fourteenth Finance Commission (FFC) award period 2015-20.

Key recommendations:

The Finance Commission is required to recommend the distribution of the net proceeds of taxes of the Union between the Union and the States (commonly referred to as vertical devolution); and the allocation between the States of the respective shares of such proceeds (commonly known as horizontal devolution).

With regard to vertical distribution, FFC has recommended by majority decision that the the States’ share in the net proceeds of the Union tax revenues be 42%. The recommendation of tax devolution at 42% is a huge jump from the 32% recommended by the 13th Finance Commission. The transfers to the States will see a quantum jump. This is the largest ever change in the percentage of devolution. In the past, when Finance Commissions have recommended an increase, it has been in the range of 1-2% increase. As compared to the total devolutions in 2014-15 the total devolution of the States in 2015-16 will increase by over 45%.

The consequence of this much greater devolution to the States is that the fiscal space for the Centre will reduce in the same proportion. As recorded in Chapter-8 of FFC’s Report, amongst other demands of the States, the States had demanded both an increase in share of tax devolution, and a reduced role of CSS.

FFC has taken the view that tax devolution should be primary route of transfer of resources to States. It may be noted that in reckoning the requirements of the States, the FFC has ignored the Plan and Non-Plan distinction; it sees the enhanced devolution of the divisible pool of taxes as a “compositional shift in transfers from grants to tax devolution” (Para 8.13 of FFC Report). Thus, basically the FFC Report expects the CSS, in fact Central assistance to State Plans as a whole, to reduce and be replaced by greater devolution of taxes.

Keeping in mind the spirit of cooperative federalism that has underpinned the creation of National Institution for Transforming India (NITI), the Government has accepted the recommendation of the FFC to keep the States’ share of Union Tax proceeds (net) at 42%.

In recommending horizontal distribution, the FFC has used broad parameters of population (1971) and changes of population since, income distance, forest cover and area.

The Finance Commission is also required to recommend on ‘the measures needed to augment the Consolidated Fund of a State to supplement the resources of the Panchayats and Municipalities in the State on the basis of the recommendations made by the Finance Commission of the State’.

FFC has recommended distribution of grants to States for local bodies using 2011 population data with weight of 90% and area with weight of 10%. The grants to States will be divided into two, a grant to duly constituted Gram Panchayats and a grant to duly constituted Municipal bodies, on the basis of rural and urban population.

FFC has recommended grants in two parts; a basic grant, and a performance grant, for duly constituted Gram Panchayats and municipalities. The ratio of basic to performance grant is 90:10 with respect to Panchayats and 80:20 with respect to Municipalities.

FFC has recommended out a total grant of Rs 2,87,436 crore for five year period from 1.4.2015 to 31.3.2020. Of this the grant recommended to Panchayatas is Rs 2,00,292.20 crores and that to municipalities is Rs 87,143.80 crores.

FFC has recommended that up to 10 percent of the funds available under the SDRF can be used by a State for occurrences which State considers to be ‘disasters’ within its local context and which are not in the notified list of disasters of the Ministry of Home Affairs.

I definitely enjoying every little bit of it. It is a great website and nice share. I want to thank you. Good job! You guys do a great blog, and have some great contents. Keep up the good work. IAS Coaching in Delhi

ReplyDelete